Mark Twain once wrote, “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.” According to historians, the groundwork for the New Gilded Age began in 1990. Nearly 30 years later, the age of the “robber baron” industrialist and the cutthroat financier has returned. Since that time, there are few industries that have seen the magnitude of disruption that housing and retail have endured. Nearly 26,000 stores have closed in the past three years; 2019 will double 2018’s closures. There are echoes of this bifurcation throughout the physical and digital spaces of commerce. Contrary to popular opinion, retail isn’t dying. Instead: changes in earnings, increased debt loads, and decreased consumption rates are beginning to polarize some consumers. The middle is being squeezed and retail failed to anticipate this socio-economic shift.

“The retail reckoning has only just begun.” Those are the words of reporter Jack Hough who released a blockbuster, paywalled report for Barron’s. But reckoning and death are not necessarily synonyms in this context. Retail is not dying, it is bifurcating. In The Ballad of Victor Gruen, the boom and bust of retail real estate is explained through the lens of socio-politics and tax policy:

According to CNBC reporter Lauren Thomas, apparel mall retail profits are at recession levels. As of June 2019, Macerich, Simon Properties, Kimco, Washington Prime Group, and Taubman properties are trading at five-year lows. There aren’t enough viable challenger brands (DTC) to fill the 67,000+ store closures projected by 2026. So, it’s difficult to determine whether or not an American retail empire built on post-war consumerism, suburbanization, and accelerated depreciation will return to its former glory. But when we wonder how the “retail apocalypse” happened, look to 1954.[1]

Per capita, America is over-retailed; it always has been. But for nearly 60 years of suburban retail expansion, it seemed as though the industry would never contract. According to Randal Konik, an analyst with Jefferies: “There are about 1,350 enclosed malls in the United States but only 200 to 400 are needed.” But while retail stores shutter, sales are expected to grow 3.5% to $3.7 trillion. According to reports by UBS, it may take ten years to reach the equilibrium (1,350 to 200). The investment bank forecasts 75,000 additional stores closing in that time.

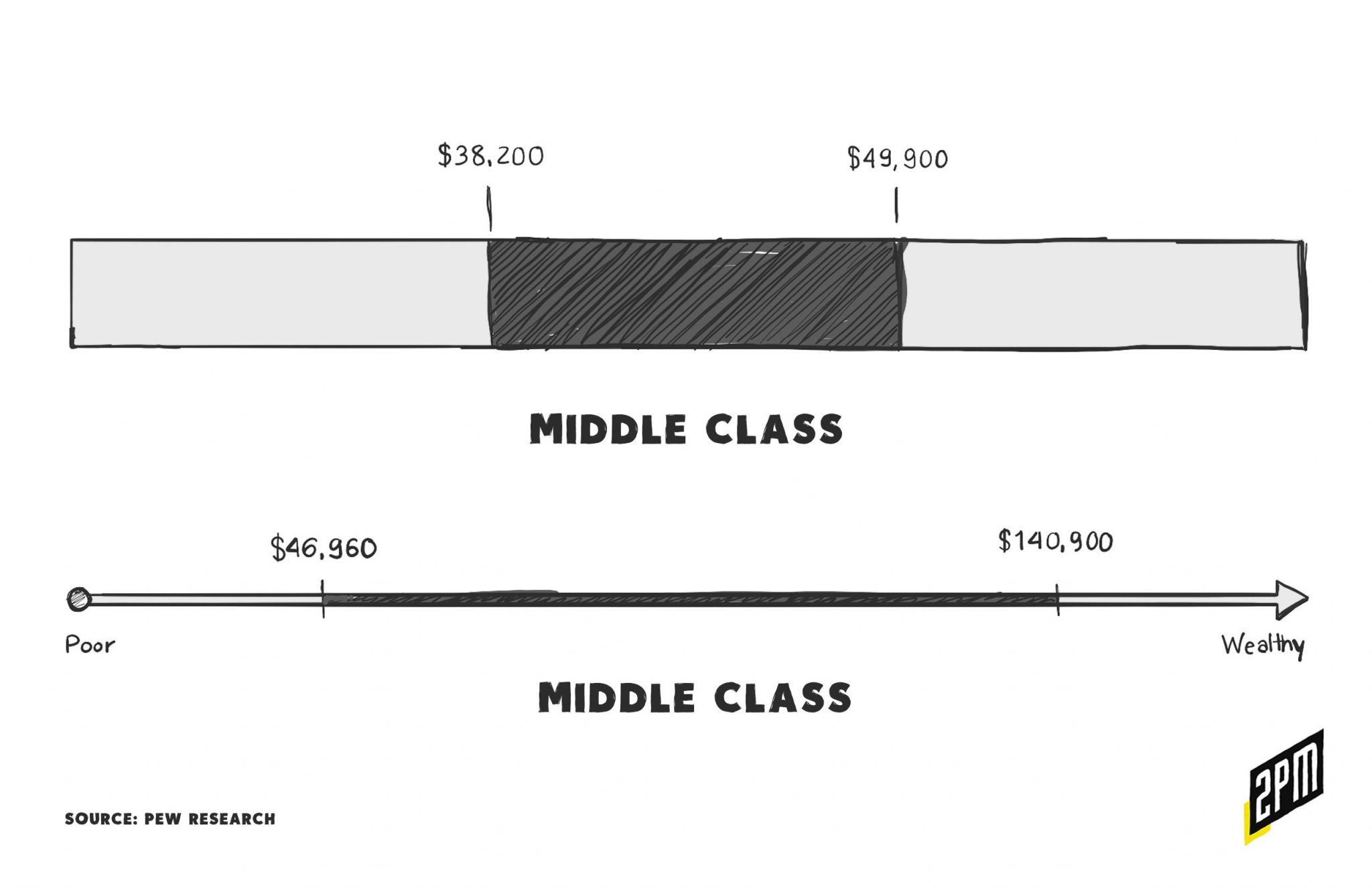

To better understand who the store closures are targeting, we must first consider the definition of the middle class – a shrinking cohort of the American consumer. There’s a great chance that if you’re reading this, you are statistically in the upper middle and wealth classes and gaining. That group earns greater than $140,901 in annual household income.

But for many hard working, middle Americans, something is lost in translation. With inflation, under-employment, rises in college tuition, mounting consumer debt, and healthcare costs – typical consumption has fallen. And families who earn a comfortable wage are living closer to the lower end of the middle-class range or below. In short, levels of wealth are polarizing and retail’s bifurcation is following suit.

Understanding the Gilded Age

The times of mining bonanza kings, railroad barons, merchant princes, bankers, generational trusts, and utility tycoons were rife with brute capitalism and a stark economically inequality that America hadn’t seen before. The country began to lead the world in the production and refinement of valuable goods and services. For the select few who benefited, new, economic monarchies were forged. For everyone else, life seemed more like scene from Sinclair’s “The Jungle.”

If you’ve ever had the good fortune of visiting Newport, Rhode Island – you’d recognize something peculiar: The Gilded Age presents itself in certain areas of the city like the era was never replaced by the middle-class boom. Between 1870 and 1900, three of the largest and most extravagant homes in America were constructed along the shores of the beautiful New England city. Of these palatial homes is what many consider the crown jewel: The Breakers. On 14 acres, the 65,000 square foot mansion serves as an archetypal memory of the age of industrialism. Cornelius Vanderbilt II bought the land for $450,000 in 1885 and finished construction on the 70+ room “summer cottage” in 1895.

As a student, I walked the halls of The Breakers with several of my classmates. We’d never seen anything like it before. Frankly, I was in shock. Growing up squarely in the middle class, I could barely imagine living in 4,000 square feet. But in the structure that harkened to the Italian renaissance, we marveled at a family’s home that spanned an entire acre of land. I didn’t know that this level of wealth existed and I surely had yet to see any of modern derivatives of that boom’s past. Castles were for history books and midieval films, or so I thought.

The rich get richer and the poor get – children.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

There are a number of Gilded Age-era homes across the United States; many have been repurposed into public buildings and monuments to the era. San Francisco has the mansions of their Big Four. Just a ways away, you’ll find the Hearst Castle. Connecticut is home to the Lauder Greenway estate. Massachusetts has The Mount. And of course, the streets of New York are peppered with homes like the Arden, Indian Neck, Olana, and Woodlea – the now-home of the Sleepy Hollow Country Club. In all, there are nearly 80 homes of this caliber in America. Not one was built after Jay Gatsby’s 1920s. That is, until recently.

There’s a paragraph in the recently published The Triumph of Money in America by Jack Beatty:

But, brazen as it was, inequality then conformed to the pattern of the unequal past. Not so inequality in what publications from the Atlantic Monthly to Seattle Weekly have denominated the “New Gilded Age,” when for every additional dollar earned by the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution, the top .01 percent earn $18,000. From 1950 to 1970, they erned $162. […] Paul Krugman notes, “Not since the Gilded Age has America witnessed a similar widening of the income gap.

The Gilded Age was a salicious spectacle of glory and tragedy. It seems that we are on the precipice of another flashpoint, where years of quiet build-up led to an “aha!” moment. Housing, mounting middle-class consumer debt, and retail trends all seem to point in that direction. Consider last mile delivery services like DoorDash or GrubHub, a luxury experienced by the upper-middle and wealth classes. But a job that takes advantage of the underemployed – many of whom are likely white collar professionals fighting to remain somewhere in the depleting middle.

There is a polarization of American wealth and it’s progressing at a dizzying pace. Look no further than San Francisco, where the newly homeless camp against the walls of four and five star hotels. The dichotomy is striking. Or consider New York City, where there may be slightly less of a wealth disparity (to the blind eye). Yet, the city’s private helicopter traffic is growing noisier while the subway system is failing many who are fighting to remain in the middle class. There are as many last mile workers on the streets of New York as there are pedestrians at times. A noticeable number of New York’s miles of retail storefonts lie vacant.

In 2018, USA Today reporter Rick Hampson wrote: “That time (roughly 1870-1900) shares much with our time: economic inequality and technological innovation; conspicuous consumption and philanthropy; monopolistic power and populist rebellion, […] and change — constant, exhilarating, frightening.” Understanding the mirrored socio-economic patterns of then and now should profoundly impact the retail operations of today.

Gilded AGE 2.0 And Modern Retail

Sears, the once-famed retailer earned its beginning in the Gilded Age. Richards Sears, a railroad worker, founded R.W. Sears in Minnesota. Operating as a reseller of jewelry and watches, early success moved the business to Chicago where he met and hired Alvah Roebuck. The retail founder and the watchmaker built an innovative business: they’d own products and brands and sell direct to consumer. A predecessor of eCommerce, today. On the heels of direct-sales and catalogue success, the retailer went public in 1906 [2].

Sears went public with preferred shares selling at $97.50 each, or more than $2,500 now. Goldman Sachs managed the offering. That year, Sears also opened a mail-order distribution center on Chicago’s West Side that, with three million square feet of floor space, was among the largest buildings of its kind in the world.

The boom of Sears’ brick and mortar growth relied the boom of rural and suburban penetration throughout America. Nearly sixty years of fortune followed. Richard Sears adjusted for the times. A business built for the wealthy became a symbol of the burgeoning middle-class. He saw the opportunity, I suppose.

Fast forward to 2019 and retail’s lines of my demarcation are clear as ever. Online retail has been adopted by nearly a quarter of Chinese citizens and across the country’s economic strata. In the United States, the makeup of online retail customers skews towards the affluent. Amazon Prime’s membership boasts over 110 million users, or a third of all of American households. Of all internet consumers, 66.3% of those who earn over $150,000 use Amazon Prime. Just 31.6% of those who earn $35,000 annually have purchased the membership.

The suburbs are overstored and undershopped, and experts say only the top 20% of malls are thriving.[WWD]

Online retail and “Tier A” malls attract an affluent consumer. Off-price physical retailers and “Tier C” malls skew towards the economically-distressed. Between 2018 and 2019, the following specialty retailers have shuttered en masse: Nine West, Claire’s, Brookstone, Samuel’s, Mattress Firm, Sears, David’s Bridal, Charlotte Russe, Payless, Gymboree, Topshop, J. Crew, J.C. Penney, Pier 1 Imports, and DressBarn.

More closures are to come. Of them: GAP and L Brands will accelerate closures, further diminishing middle class retail. Not only are we witnessing a polarization of American wealth at a dizzying pace, it is now reflecting in retail real estate. The institutions for the affluent have remained steady, in some cases contributing to a growing retail sector. The institutions for the economically-distressed are also doing quite well. Historically, off-price and luxury retail were at the periphery. If these trends continue, these two cohorts may become the collective majority.

There are implications for digital-natives. Consider the rising customer acquisition costs of today’s direct to consumer business. Facebook, Instagram, and Google’s advertising inventory have remained static while the volume of DTC founders who launch companies continues to rise. Rather than a go-to-market that appeals to a growing number of modern luxury consumers and HENRY’s (high earners, not rich yet), many DTC brands optimize message, branding, and ad spend to reach a contracting number of middle-class consumers. Or worse, off-price consumers who’ve yet to fully adopt online retail as a method of consumption. It’s unclear whether or not this dynamic is contributing to a rising CAC but the shifting dynamics of an audience should concern marketers.

Meanwhile, off-price digital natives like Brandless and Jet.com have struggled as they focus on forms of bargain-driven promotion. While over 100 million Americans use Amazon Prime, we’re still at 11-13% of retail being attributed to online transactions. The United States is still in the early stage of eCommerce adoption; as such, off-price consumers continue to lag behind in the adoption curve. It’s reasonable to assume that this contributed to what may have been an overestimation of total addressable market (TAM) for retailers in the off-price category. Brandless has since adjusted their strategy to appeal to more affluent shoppers. “The average order value today needs to move from $48 to probably $70 or $80,” the words of Brandless’new CEO who has committed to charging more for products, leaving behind the company’s bargain basement strategy.

This era has begun to reveal sharp contrasts in how Americans approach the consumption of goods and services. Net consumption continues to grow despite a catastrophic number of store closures. Some in retail and media are quietly recognizing that the most competitive approach to growth is the pursuit of the modern luxury consumer – a cohort that seems to be invulnerable to these shifts. Products have become more exclusive, with higher quality production, and superior service. As online retail penetration continues to grow from 11% to levels resembling China’s, off-price retailers will begin to see more success – a notion that should bode well for Walmart, Costco, and others.

While history doesn’t repeat itself, it does rhyme. The economically-disadvantaged deliver food, novelties, alcohol, and commodities to urban sprawls and gated suburbs – within the hour. Across the country, the net worths of the top 1% have become noticeable as conspicuous consumption of products and services have risen; the rise of platforms like StockX, Hodinkee, and Uncrate demonstrate this. For the top .01%, there are more 40,000+ square foot homes than there were in the Roaring 20’s. Retail is responding to economic realities of today. Wealth is galvanizing; retail strategies should adjust to meet the shifts head on.

The term retail apocalypse has always been an uncomfortable generalization to make. This research suggests that it’s also an innacurate one. Rather, Gilded Age 2.0 is a casualty of the middle class; a consumer that emerged in response to the industrial and financial booms of the late 19th century. The early 21st century resembles a time when the middle barely existed. It was an unfortunate time of boom or bust, feast or famine. For commerce and its adjacent industries – 2.0 is a correction that can no longer be ignored.

Research and Report by Web Smith | About 2PM