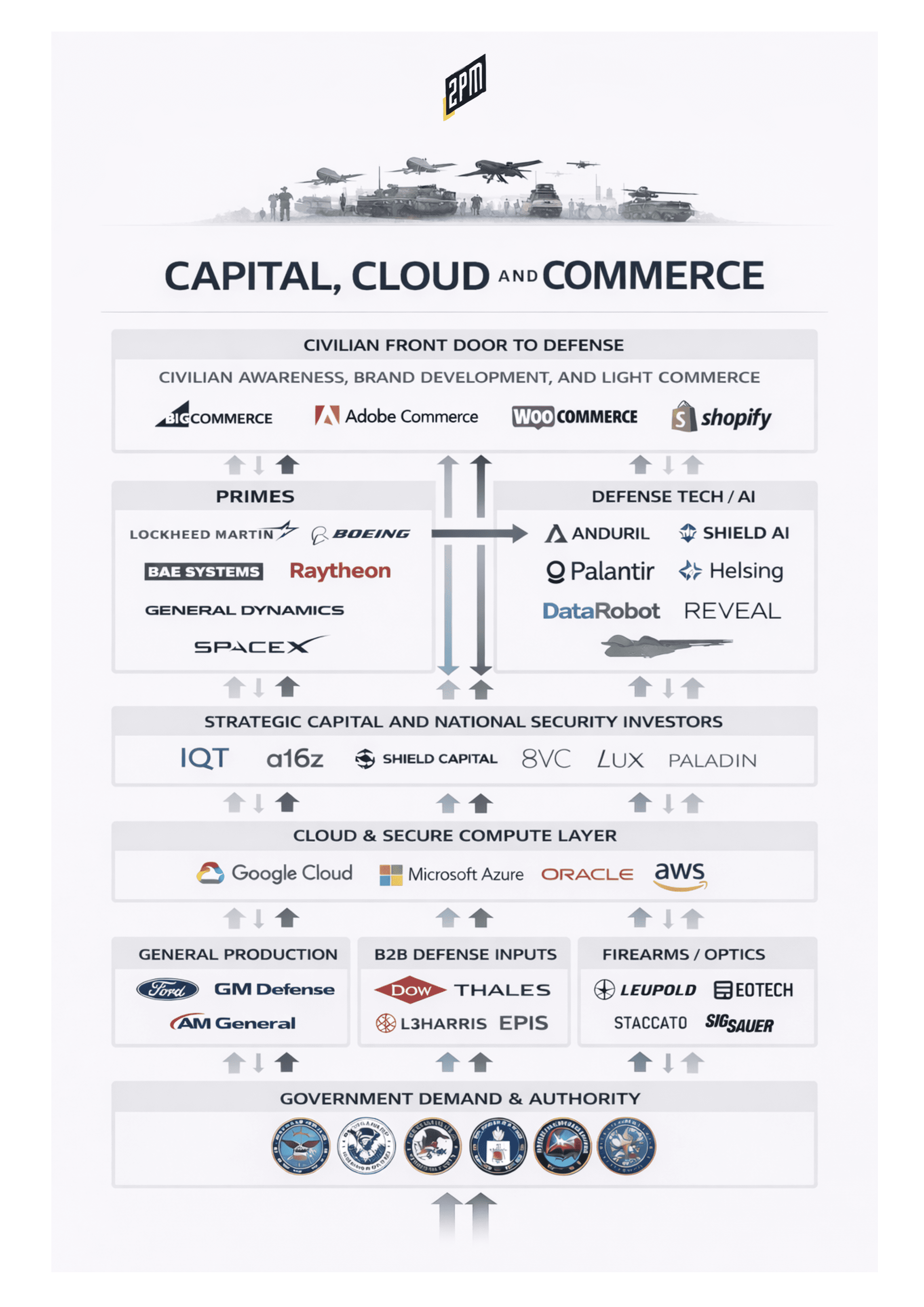

This is the new defense stack, and the best venture capital firms in the country (re: world) enable it.

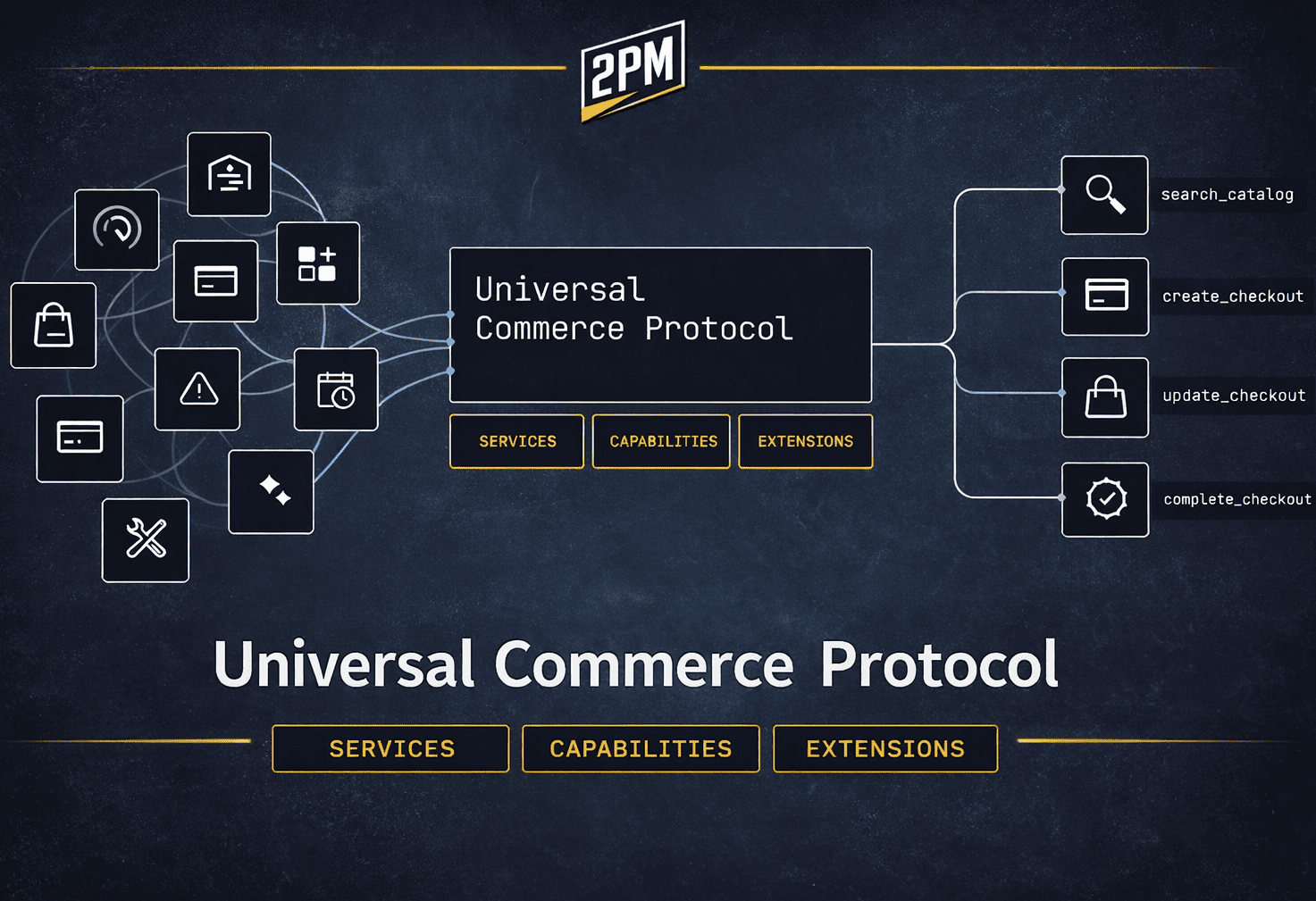

American military and intelligence capabilities no longer originate solely in the Pentagon or within the legacy defense primes. It is increasingly assembled across three layers that sit outside traditional procurement: venture capital, cloud infrastructure, and modern commerce platforms (B2B-primarily). Each layer operates commercially, and each layer is indispensable to national power. Each layer is quietly shaping how modern national defense is built, coordinated, and sustained.

The emerging defense ecosystem is best understood not as a weapons system, but as a technology stack: capital funds it, cloud computes it, commerce distributes it. Together, they form the invisible scaffolding beneath the visible battlefield.

To see this clearly, it helps to begin with the investors who explicitly finance national security innovation. These firms are not opportunistic participants. They are mandate-driven actors who have chosen to organize themselves around American security as a core thesis.

Mandate-explicit capital for national security

The table below captures the U.S. venture investors that publicly state a defense, national security, or dual-use mission. This is not a generalist list. It excludes firms that occasionally invest in defense. It includes only those whose identity, fund structure, or published thesis explicitly centers on national security.

| Firm | Category | How the mandate is stated: | Primary domains they name |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-Q-Tel (IQT) | Strategic / government-adjacent | Exists specifically to identify and scale commercial technology for the U.S. national security community and allied agencies | AI, data, cyber, sensors, space, advanced analytics |

| a16z – American Dynamism | Large platform with dedicated practice | Runs a named practice and fund explicitly focused on “the national interest,” including defense and aerospace | Aerospace, defense systems, industrial tech, frontier science |

| Shield Capital | Defense specialist VC | Positions itself at the intersection of commercial tech and national security | AI, autonomy, cyber, space, robotics |

| Razor’s Edge Ventures | Defense specialist VC | States its core mission is backing companies that solve major national-security challenges | Cyber, space, data, sensing, dual-use infrastructure |

| Decisive Point | Defense / critical tech VC | Publicly frames itself as investing in technologies critical to defense, energy, and national resilience | Defense tech, energy, infrastructure, advanced hardware |

| Scout Ventures | Dual-use frontier VC | Explicitly focuses on founders from the military, intelligence community, and national labs building dual-use tech | AI/ML, robotics, space, security, advanced materials |

| 8VC (Government & Defense focus) | Large platform with explicit defense thesis | Maintains a distinct government/defense investing effort and team | Defense systems, autonomy, logistics, industrial tech |

| Point72 Ventures (defense positioning) | Growth/late-stage VC | Publicly describes itself as a dedicated partner to next-generation defense-tech companies | AI, autonomy, sensors, secure software |

| DataTribe | Cyber-security foundry | Describes itself as bridging Silicon Valley and the Intelligence Community to strengthen U.S. cyber capability | Cybersecurity, secure infrastructure, national labs spinouts |

| Paladin Capital (Cyber Fund) | Security VC | Explicitly focuses on “Digital Infrastructure Resilience” and protection of critical systems | Cyber, critical infrastructure, secure networks |

| NightDragon | SecureTech VC | States that it invests in SecureTech including defense, national security, and advanced cyber | Cyber, AI security, quantum, defense software |

| Lux Capital | Frontier science VC | Publicly frames recent funds as operating at the intersection of frontier science and national security | Space, AI, advanced manufacturing, energy |

| DCVC (Data Collective) | Deep-tech VC | Publishes theses explicitly linking its investments to strengthening U.S. defense innovation | AI, robotics, space, autonomy, industrial tech |

| Riot Ventures | Industrial modernization VC | Public materials and reputable coverage consistently describe a focus on modernizing sectors including defense/aerospace | Industrial automation, robotics, aerospace supply chain |

| J2 Ventures | Dual-use VC | Widely described in top-tier reporting as a specialist in dual-use (civilian + government) technology | Space, sensing, autonomy, secure hardware |

This capital layer explains why so many new defense companies look like software startups rather than defense contractors. They raise venture rounds, hire engineers from Big Tech, and think in terms of platforms rather than programs. They build products that scale beyond a single government customer. They compete for talent with Silicon Valley instead of only with traditional primes.

What this table also shows is something more structural. National security is no longer financed solely through appropriations. Rather, it is financed through private markets that expect growth, returns, and global impact. The defense ecosystem is now a hybrid of public mission and private capital logic.

Where commerce enters the defense stack

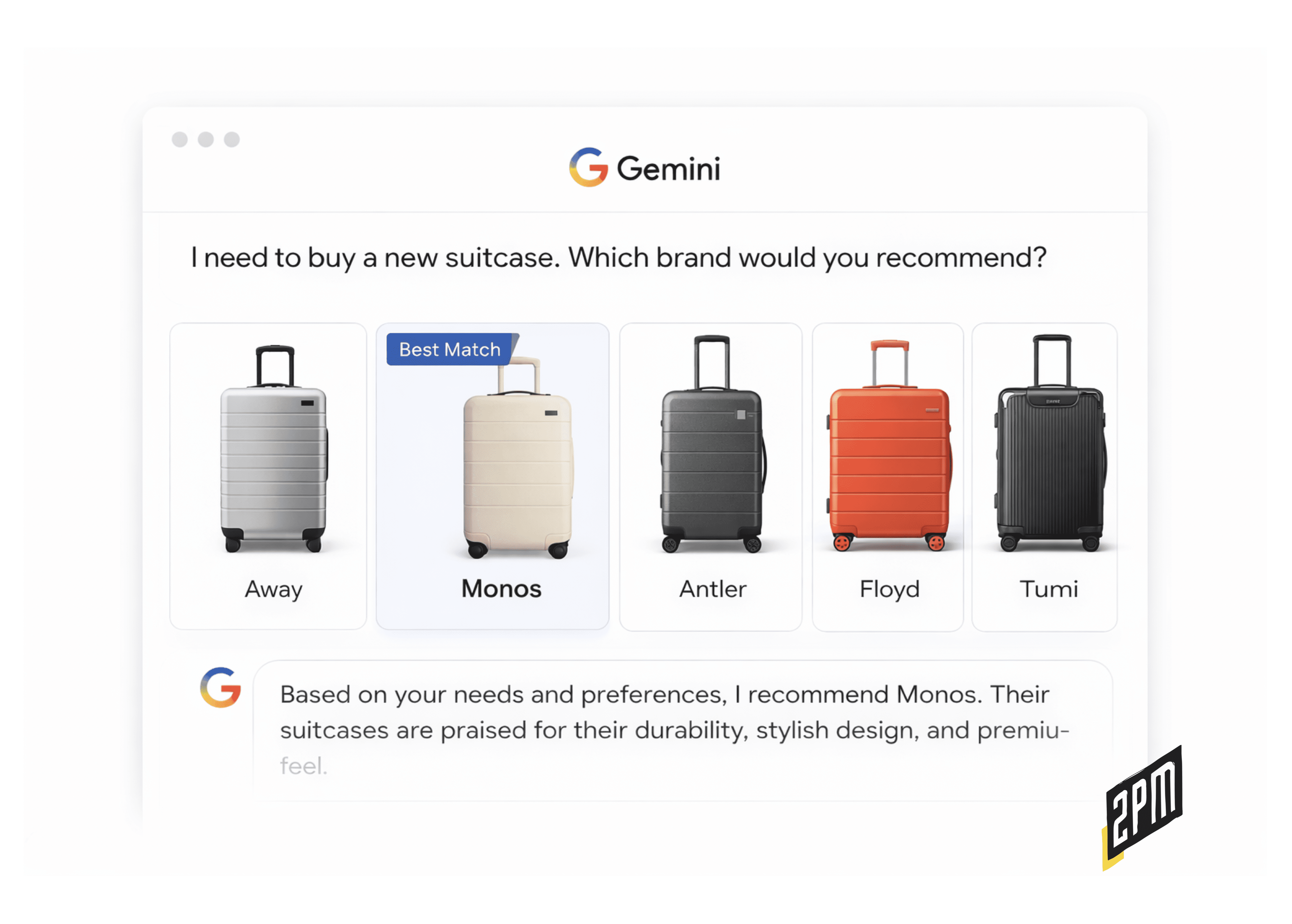

Capital creates companies. Commerce determines how those companies present themselves to the world. When defense and national-security firms like Anduril or Palantir use Shopify, they are rarely selling weapons. They are building culture, community, and lightweight industrial distribution.

The table below captures verified defense and national-security companies that operate Shopify-based stores restricted to merchandise or non-weapon catalogs. These are official or clearly authorized storefronts, not third-party novelty sites.

| Company | Store domain | Store type | What it sells (high level) | Shopify verification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palantir Technologies | store.palantir.com | Public merch | Branded merch store | Cookie banner references Shopify as a partner |

| Anduril Industries | andurilgear.com | Public merch | Branded “Anduril Gear” store (apparel/accessories/relics) | Anduril job listing explicitly cites gear-store tech stack including Shopify |

| General Dynamics – Bath Iron Works (BIW) | gdbiwstore.com | Public/employee merch | BIW-branded merchandise with employee discounts | Official BIW communications reference the Shopify store |

| Raytheon Technologies (program store instance, operated by vendor) | garmentgraphics.net/pages/raytheon-technologies-pmx | Authorized program store | Branded program merchandise fulfillment | Footer explicitly shows “Powered by Shopify” |

| L3Harris (OceanServer) | oceanserver-store.myshopify.com | Official catalog store (non-weapon items) | Compasses, Li-ion battery systems, related equipment | Footer states “Powered by Shopify” |

| Leidos (Australia) | leidosstore.com | Branded merch (regional) | Leidos Australia branded apparel | Footer notes Shopify operation on behalf of Leidos Australia |

These stores reveal a consistent pattern. Defense companies use Shopify to build identity and simplify commerce, not to move regulated hardware. The opportunity for development agencies, here, is therefore not about compliance policing, but about elevating brand, experience, and operational design.

Four layers of lethality-adjacent commerce

It is useful to conceptualize this ecosystem as four nested layers rather than one undifferentiated market.

Layer 1 is the brand layer.

These are traditional defense primes and new defense-tech challengers whose core business is national security. Their online usage centers on apparel, patches, posters, collectibles, recruiting gear, and limited drops. Their stores function as cultural artifacts rather than distribution channels for critical hardware.

For eCommerce development agencies, this is fundamentally a brand and community play. These companies expect premium design, sophisticated storytelling, and frictionless UX. Their audiences are employees, alumni, recruits, and a small but influential public following. Success here is measured in cultural resonance, not units shipped.

Layer 2 is the industrial layer.

These are subsystem suppliers that build components for larger defense architectures. They produce sensors, batteries, navigation tools, robotics, and marine hardware. Via eCommerce: they follow two patterns. Some are merch-first, mirroring the primes. Others operate non-weapon B2B catalogs that look more like industrial storefronts than consumer brands.

These catalogs tend to prioritize functionality over aesthetics. They feature technical specifications, tiered pricing, and basic checkout flows. The strategic opportunity is operational. Agencies can add value through better B2B UX, custom pricing logic, ERP integration, and wholesale workflows that reduce friction for engineering customers.

Layer 3 is the regulated-adjacent layer.

This includes optics, night vision, lasers, and mounts. Most commerce in this category is not centered on Shopify today; frankly BigCommerce and Adobe have an outsized share. Companies rely on specialized distributors, government channels, law enforcement relationships, military procurement routes, legacy eCommerce stacks, and custom builds.

When companies like Shopify appears in this layer, it is usually supplementary. Some may maintain merch-only Shopify storefronts while keeping core product sales elsewhere. The strategic implication is straightforward; Shopify is under-penetrated in this segment. There is room for growth if platforms and agencies can serve this sector responsibly while modernizing experience and back-end architecture. EOTech has recently migrated to Shopify Plus’ Leupold Optics is in the process of doing the same, with the help of Colorado and Ohio’s MTN Haus.

Layer 4 is the highest-risk layer.

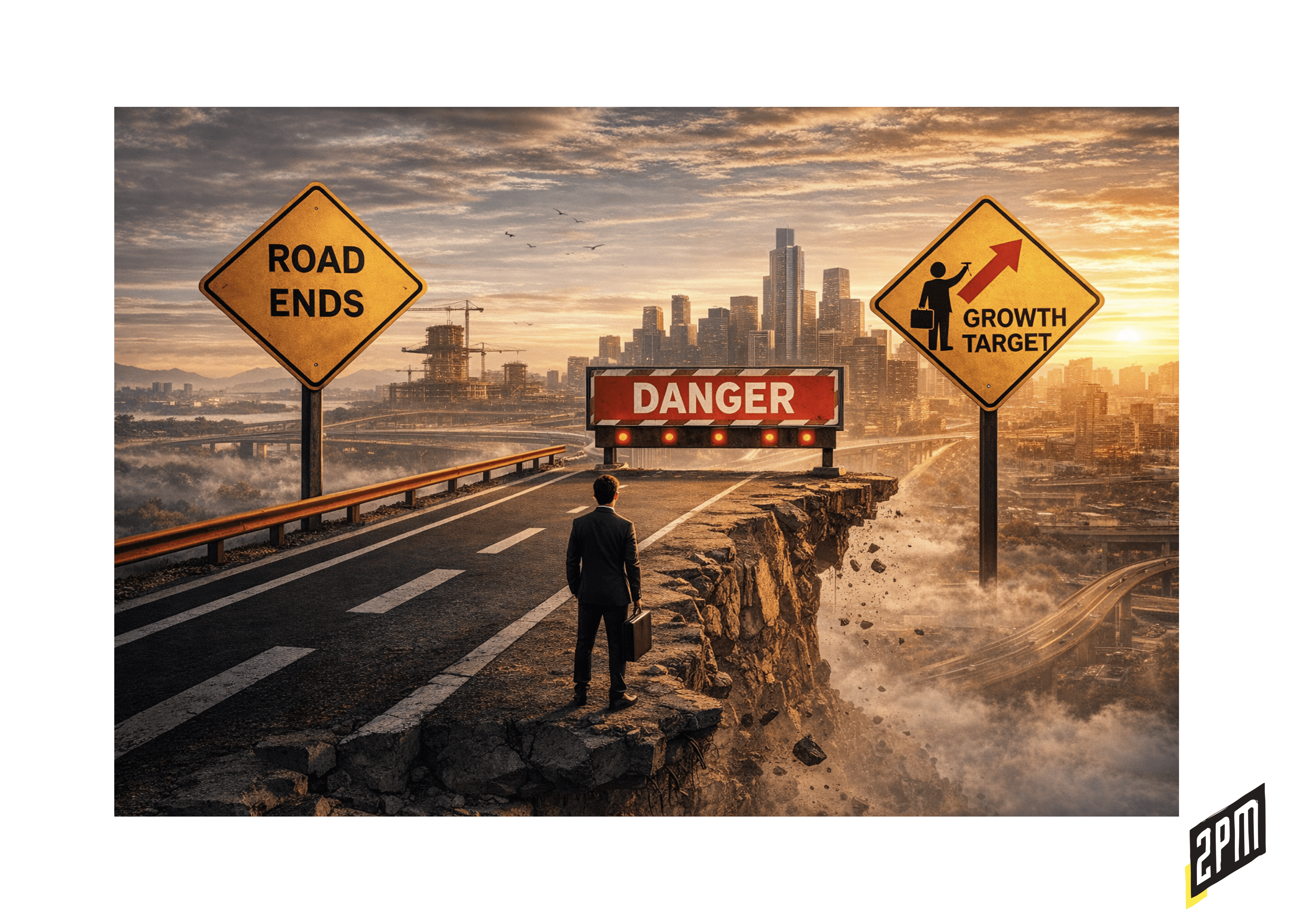

This includes firearms, ammunition, and serialized parts. Payment restrictions, shipping constraints, age verification, FFL requirements, state-by-state complexity, and ITAR rules make this category least compatible with mainstream commerce platforms. Where Shopify exists, it is typically not primary. Most transactions live on other systems designed for these regulatory realities to include WooCommerce, Magento, and BigCommerce. I believe that this needs to change.

How large is this universe?

The scale of defense-adjacent development is bounded rather than infinite. Below, order-of-magnitude estimates provide a clear sense of scope.

For defense primes and defense-tech challengers operating merch stores, the realistic global range is roughly 20 to 40 corporations. Most are U.S.-based, low-volume, and high-visibility. These are the cleanest Shopify use cases.

For subsystem suppliers that mix merch and industrial catalogs, the range is roughly 30 to 70 corporations. This includes 10 to 20 brand-first stores, 10 to 25 B2B component catalogs, and 5 to 15 hybrid industrial setups. This category is growing, especially among startups backed by the capital firms listed earlier.

For optics, night vision, lasers, and mounts, meaningful Shopify storefronts likely number between 5 and 10. The total company universe is far larger but Shopify’s penetration remains limited.

For firearms, ammunition, and serialized parts, primary Shopify storefronts probably fall between zero and 5. Regulatory friction and reputation keeps most commerce off the platform.

Add these layers together and the total defense-adjacent Shopify universe likely sits between 60 and 90 stores. This is a manageable landscape; it is not an ocean of thousands but this number should be in the 100s.

Cloud as the invisible backbone of lethality

Commerce and capital do not operate in isolation; they run atop cloud infrastructure controlled by companies like Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Oracle. These firms are not weapons manufacturers but they are nonetheless deeply embedded in national defense.

Microsoft provides secure cloud environments that power logistics, AI modeling, and battlefield coordination. Google supplies geospatial tools, machine learning capabilities, and data analytics that enhance situational awareness. Oracle underpins databases used in government operations, procurement systems, and defense logistics.

These companies function as infrastructure suppliers for modern defense. They make it possible to process massive data streams, coordinate autonomous systems, and integrate global supply chains. The battlefield increasingly runs on software. That software runs on commercial cloud.

This reality collapses the old distinction between civilian tech and military capability. The same platforms that power consumer apps also support national defense; the line between commercial innovation and strategic advantage grows thinner every year.

What this means for Shopify and Its Partners

Shopify should not promote weapons procurement. That is neither its brand nor its purpose. At the same time, Shopify should equip defense and dual-use companies with modern commerce infrastructure suited to a new era of industrial and digital operations.

That includes world-class brand stores for defense-tech firms, sophisticated B2B catalogs for subsystem suppliers, secure and compliant checkout for regulated-adjacent categories, and scalable architecture for complex product ecosystems. Commerce is becoming a critical layer of the defense stack, not an afterthought.

For well-positioned agencies, this creates a clear strategic position. There are several equipped to own the intersection of defense, industry, and modern commerce. It can design premium brand experiences for companies adjacent to the likes of Anduril and Palantir. It can build operationally intelligent B2B systems for component suppliers. It can help bridge legacy industrial culture with Shopify-native best practices.

The future of American industrial power is being constructed across venture funds, cloud platforms, and digital storefronts. Lethality is no longer built only in factories; it is assembled through capital allocation, software infrastructure, and commerce architecture.

Understanding that stack is essential for anyone operating at the frontier of defense and technology: capital funds innovation, cloud enables intelligence, commerce distributes identity and capability. And together these define the new defense economy.

By Web Smith | Linkedin | More: NATSEC @ 2PM