The discussion between us was slow and every answer labored. It was difficult to tactfully explain the concept of an “unnecessary wait.”

There’s always a wait.

Modern Retail editor Cale Weissman wanted to understand the Black perspective of those of us in eCommerce. I didn’t have many answers for him. I worked to moderate my responses, struggling to mask volumes of persisting frustrations within the digital industries. At one point, Weissman asked for a list of venture-backed founders in the direct-to-consumer space. There was, of course, the obvious answer. Tristan Walker rolls off the tongue. But I didn’t have a novel response in that moment and I was ashamed of that. There are so few Black professionals in this space. For the vast majority of prospective executives, founders, or investors, they’re still waiting.

A portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth”, you’ll see Juneteenth celebrations from Target, Nike, Glossier, Deciem, Ford Motors, Adobe, Allstate, Altria, Best Buy, Google, JPMorgan, Lyft, Mastercard, Postmates, Tesla, SpaceX, RXBar, Spotify, Twitter, Square, Workday, Uber, and countless others. Most of it will be in vain and some of the efforts will be widely panned.

Dino-Ray “96,000” Ramos on Twitter: “.@Snapchat released a statement about their #Juneteenth filter… pic.twitter.com/KWPZnlWG3n / Twitter”

@Snapchat released a statement about their #Juneteenth filter… pic.twitter.com/KWPZnlWG3n

You’ll observe brands, people, and media commentators missing the point. You’ll see gimmicks, carefully crafted statements, and an oversimplification of a complex period in American history. Imagine our great grandchildren over-simplifying the present day.

For some of us, Juneteenth was only sort of a celebration. Imagine wanting something for your entire life and then waiting two and a half more years for that something. It’s a bittersweet celebration. For those of us who descended from those strong-minded South Texans, today is the annual reminder of their physical, mental, and emotional resilience. It’s a reminder of our inherited endurance, will, and resourcefulness. There’s always a wait. So, Juneteenth: a celebration, sure. A national holiday? Of course. But within the confines of the classrooms, offices, or neighborhoods of our American cities, Juneteenth should be a day to reflect on the waits that remain.

Grandchild of Slaves and Grandma to Me

Dorothy Smith’s grandson’s first essay remained on her bookshelf. It was an elementary school recount of Jack Roosevelt Robinson’s embattled life, the first man to cross the color barrier in Major League Baseball. I remember the essay because in 1992, it was my first time using a color printer for a school project. I recall the pride of using an image of his baseball card as the hook for a project that made me emotional, even as a nine-year-old. The eight-page report was double-spaced with size 18 font. For some reason, she was proud of that essay and it remained in her home until her passing in April of 2014. She’d critique the cadence and the word choices. She’d implore me to slow down when I read it aloud; I stuttered heavily back then. I credit our conversations for helping to heal that ailment.

Between 1992 and 2014, she’d go on to help me with a number of essays. As she got older and less capable, she’d listen to me narrate the stories that I wrote. But earlier in my life, she’d actually help me write them. A highly educated woman, she was my hero. By the end of this essay, she might be yours. One of those essays was a seventh grade report on Juneteenth’s impact on my own family. I’ll never forget her input:

The message of freedom didn’t make it all the way down here and, so, they had to wait a little bit longer. There was always a wait. There’s always a wait.

President Abraham Lincoln drafted Proclamation 95 in September 22, 1862. Imagine hearing word of this proclamation and then waiting for it to save you. It was effective, five months later, as of January 1, 1863. Imagine counting down those days to freedom. For some, the count was far longer. For that lot, their freedom was hidden by economic and political disdain for the federal order. It would be an additional two years before my relatives heard the news.

Every advocate of slavery naturally desires to see blasted, and crushed, the liberty promised the black man by the new constitution.

Those were the words of Abraham Lincoln in 1864 to Union General Stephen Hurlbut, an ally on paper but a critic in private. Even after the order, a number of states avoided the action required to fulfill the president’s wishes. According to Dorothy Smith, the population of Texas was aware of their ordered freedom long before they received it. For them, it was a painful wait. I’ll never forget the emphasis on “there’s always a wait.” These were the words of Dorothy Smith: child of laborers and sharecroppers. She was an entrepreneur, a retailer, a real estate agent, and mother to six college graduates. Dorothy was the grandchild of Texas slaves and my grandmother.

Her grandparents were born in 1858 and 1853. Dave and Sallie Draper Hill were born enslaved in Panola, a small town on the border of Texas and Louisiana. They were of the last American slaves freed by that Galveston, Texas order on June 19th, 1865. They’d later marry in 1881. According to the 1900 census, they’d go on to have 12 children. My great-grandmother was born in 1895. She’d later become an independent farmer, raising cattle, pigs, chickens. She grew and sold vegetables and she tended to a fruit tree orchard on her property. Her daughter would marry James Smith in 1944 and remain married to the Army Air Corps veteran until their passing – one year apart.

I always contemplate what earlier generations of my family would have done with real opportunity. It always seemed as though they were capable, potent, and waiting. It was Dorothy who we credit with taking matters into her own hands. She was defiant in her capitalism, her pursuit of education, her politics, her advocacy, and the opportunities afforded to her six children. She resented the idea of Juneteenth, in ways. It represented neglect and deception, a stalling of opportunity. It was the embodiment of an unnecessary wait for the opportunity to live a full life.

She stopped waiting.

The Sudden Retailer

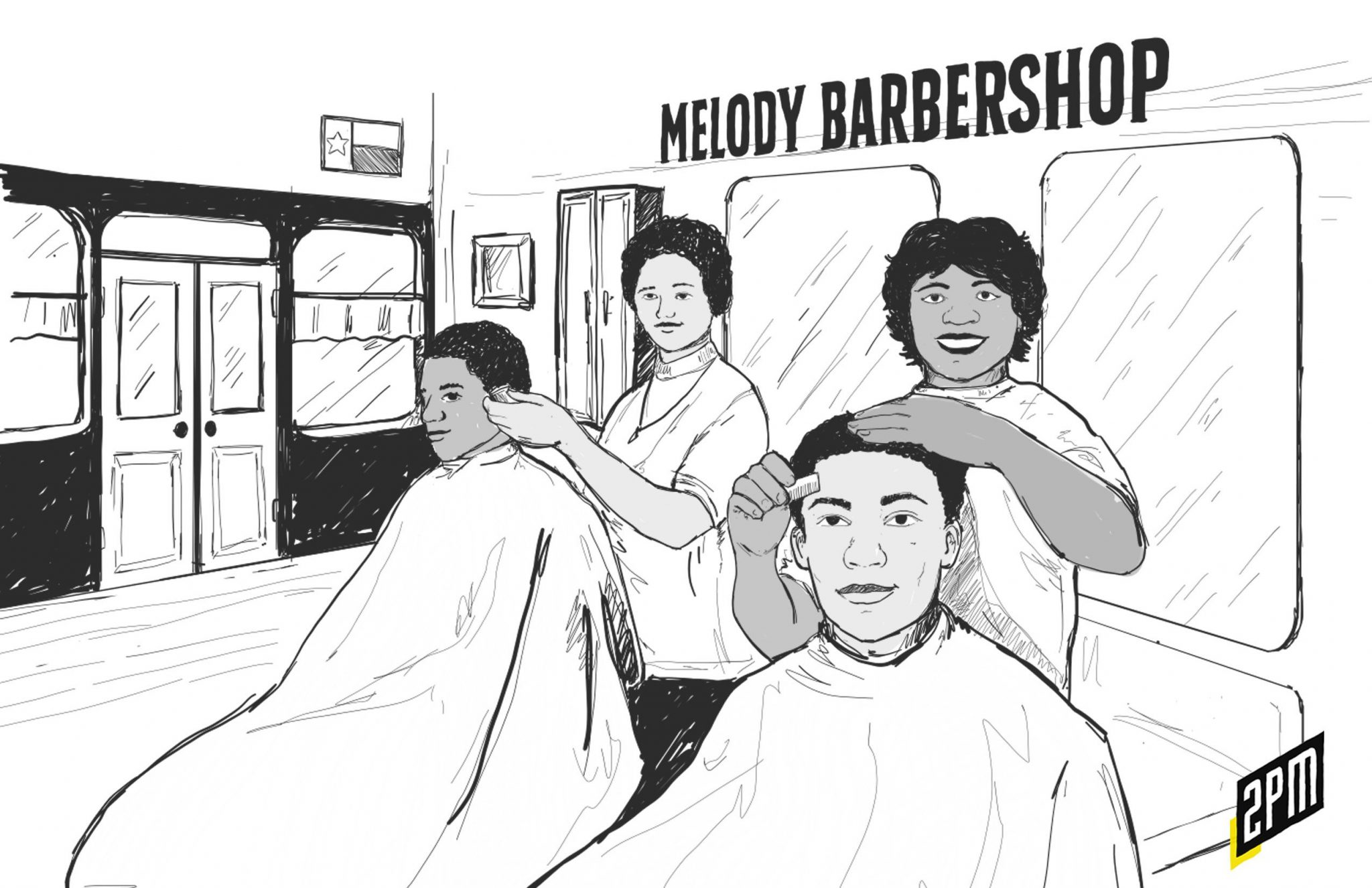

With her meager savings, she launched two businesses that operated in tandem. Both companies were within the same strip mall and they’d feed each other business for decades. A licensed barber and realtor, “Melody” became her calling card. By the mid-1950’s, the barbershop generated substantial cash flow, allowing her to hire staff and procure basic wholesale partnerships. Her storefront would double as a beauty supply retailer, amplifying her earnings by catering to an audience with few places else to shop. This should sound like a familiar strategy. Her clientele was working class and upwardly mobile, a trend that would continue throughout the Civil Rights era.

Many would eventually buy homes in the area Northeast area of downtown Houston. Melody Realty would be one of their guides. The Fifth Ward was an area where Black Americans could buy homes without political or social persecution. Regardless of one’s wealth, the city’s affluent remained deed restricted – first legally and then by proxy. The middle-class son of a Texas Instruments engineer and flight attendant, I’d later be born in that same downtrodden area in 1983. Thirty years later, the city’s deed policies remained. There’s always a wait.

Dorothy would later become one of the preferred real estate agent of her area. In this way, her storefront operated as a funnel. Her Melody brand of business blended short-term cash flows with longer-term windfalls. It changed the trajectory of our family. James, an Army Air Corps veteran, and Dorothy would send six children to colleges across the United States throughout the 1960s and 1970s. All would graduate and five would go on to have children. By the time that we were born, the idea of college was an afterthought. It was just another task for us. And so was entrepreneurship.

Dorothy would enforce a strict policy for each of her children. My father and his siblings would be required to earn their barber’s license while in high school. This sense of economic independence would propel a number of those children to impactful lives in business, religion, and medicine. Today, Melody Realty continues to operate in the Houston area, a testament to her work.

Conclusion: Ending The Wait

By the time I was born, she’d complete classes at Rice University. She was omnipresent in our lives and she stressed the importance of sacrifice. Dorothy Smith’s life had a profound impact on my own. In our home, she’s taken the form of a superhero. Imagine being born into a world that penned you for one thing and then choosing to achieve something more. She’d send six kids to school before the United States provided her the right to vote. My father was 13 when the Voting Rights Act passed. There’s always a wait.

Dorothy was uncomfortable with Juneteenth because it was symbolic of the proverbial weight of an unnecessary wait. This same concept can be applied across generations, including our own. Dorothy would argue that she was nothing special. Imagine what her parents could have done with the freedoms that Dorothy possessed. I can envision Dorothy Smith atop of our industry, if she was born during my lifetime.

The story of upward mobility in America is one of waiting. In the 1800s, it was for freedom. It the early 1900s, it was waiting for the dignity of citizenship. In the late 1900s, it was the wait for legal equality. And today, it’s the wait for equity in treatment and opportunity. We’re still in the proverbial period of waiting.

Today, we are celebrating the overcoming of adversity. It’s not intended to be a pleasant memory. I’d have preferred to celebrate no Juneteenth at all. I am sure that Sallie and Dave Hill would have agreed. When you’re deserving of opportunity, every single moment without it will feel like a decade. Now, imagine how two years of waiting may feel. The daughter of field laborers, she birthed a generation of Black professionals. Her life was a force function that bent time. There should have been more Dorothy’s in the 1950s and 1960s. There should be more of her children. We have to recognize that an unnecessary wait is just as fraught as no opportunity at all.

The hope is that, today and every day forward, we work to bend time. The leadership of the industries that define American exceptionalism should reflect America. We should provide opportunity, fill executive suites, hire the best people, invest in resilient entrepreneurs, mentor, lead, build, uplift, and provide the freedoms that some Americans take for granted.

There are more Dorothy’s than we know and some of them are waiting. The 45 second pause between Weissman’s question and my answer likely made him as uncomfortable as it made me. In a better version of our world, I would have answered his question with ease. It’s critical that we identify our own unnecessary waits. Once we do, it’s our responsibility to end those waits with opportunity. It’s the one small change that can alter the course of generations.

Essay: Dorothy’s Grandson | Editor: Hilary Milnes | Art: Alex Remy | About

Very powerful read. Thank you for writing this.

And Sapna, thanks for reading it. I know that you’re incredibly busy.

You’re such a talented and brilliant writer. Thank you for pausing and bravely delving into the hurt and frustration so that others can be better informed. It’s a generous gift.

Thank you so much for reading it! I hope that it helps.

Thank you so much for sharing this. Your Grandma must have been a truly amazing and inspiring person, and reading this I’m sad that I never got the chance to meet her. I bet Dorothy would have said that her kids and grandkids are amazing, and I think she would be right in saying that. Thank you for doing what you do Web Smith.