Temporarily unlocked. In a world increasingly driven by data, connectivity, and seamless integration of technologies, it’s no surprise that our vehicles are evolving to become the most intimate products we own. These are not just modes of transportation; they’re an extension of our digital lives, seamlessly integrated with our personal and professional activities.

In the annals of ancient mythology, the Greeks infiltrated the walls of Troy not through force, but with guile and deception in the form of a wooden horse on wheels. This iconic Trojan horse has since become a symbol of subterfuge, a strategy of infiltration under the guise of a gift. Fast forward to our digital age, and we see vehicles evolving into not just machines of transportation but highly complex mobile computing platforms. Beneath the sheen of these sophisticated interfaces lie intricate webs of power, influence, and control that have not just consumers but automakers themselves navigating a modern-day Trojan scenario.

But is this infiltration a benign integration or a strategic takeover? Drawing parallels between ancient myths and modern mobility, this essay delves into the role of Blackberry, the intricacies of automotive software, and the potential implications of having consumer-electronics giants at the wheel of our automotive future.

When researching this technological revolution, BlackBerry, once primarily known for its secure email services and qwerty smartphones, emerged as a frontrunner in facilitating the infrastructure that makes our cars smarter. According to data from BlackBerry, their QNX system, a high-performance real-time operating system (RTOS), offers automakers a top-tier level of functional safety for automotive applications. It taught me a lot about the complexity of everything from in-car entertainment systems to how we control our vehicle’s traction settings.

Recent advancements in car connectivity, such as Apple CarPlay and Android Auto, have changed the in-car experience. These systems allow drivers to project their smartphone interfaces onto the vehicle’s infotainment screen, offering navigation, media playback, and various other apps in a familiar format. But there’s more to these systems than meets the eye. But despite the rising prominence of consumer electronics giants like Apple and Google in the automotive space, it’s essential to understand that the bulk of a car’s software isn’t controlled by these companies. Advanced systems like ADAS, autonomous driving functions, and various other modules have their distinct software, adding layers of complexity and function to the vehicle’s operating ecosystem.

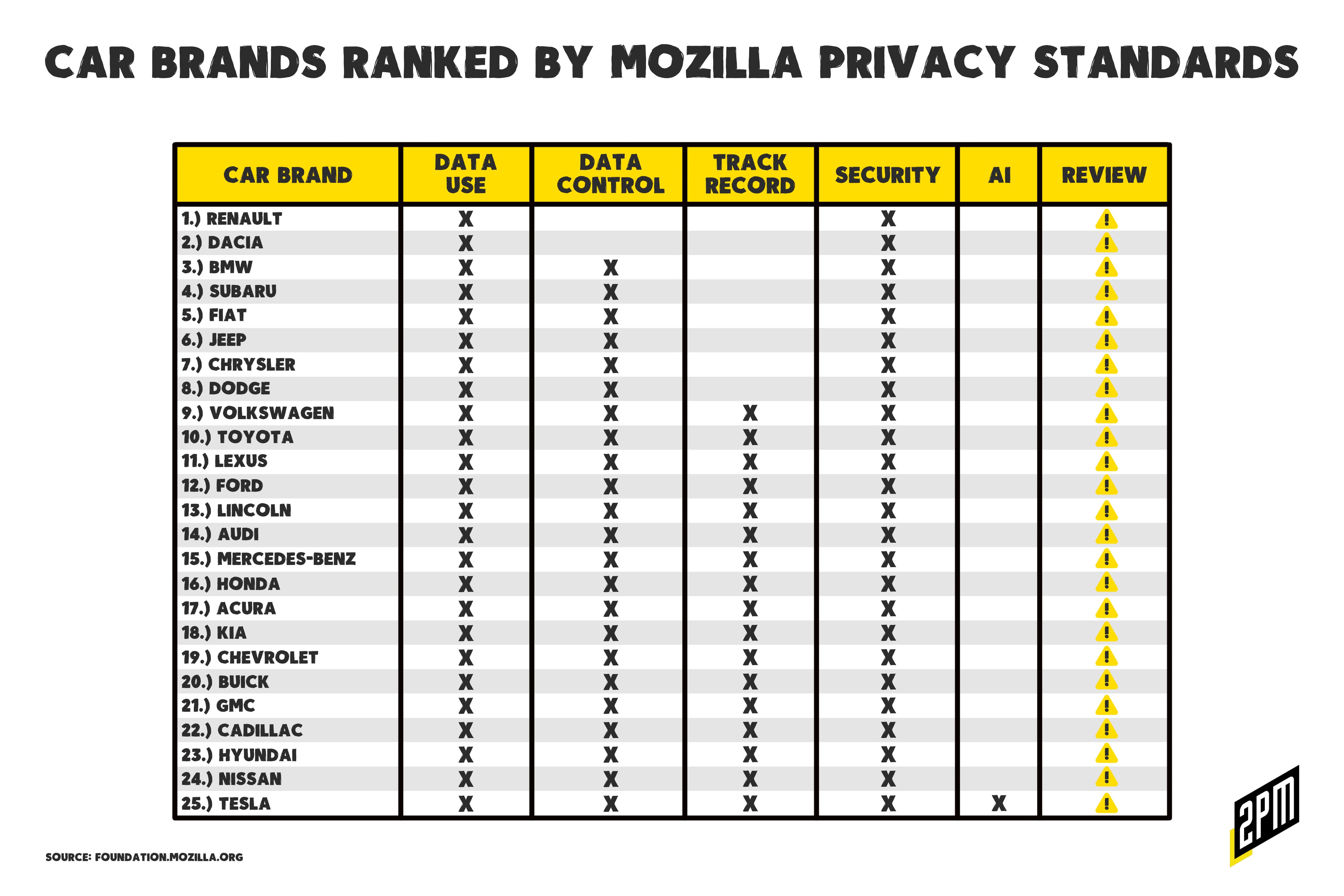

As vehicles become smarter and more integrated with our daily tech, there’s a sophisticated interplay between different software ecosystems. One of them is now under increasing scrutiny. Mozilla, once known for its eponymous internet browser, is making news for another reason.

The advent of the internet and the subsequent boom of social media platforms led to an entirely new age of advertising. Through targeted ads, companies could tap into a gold mine of personal information, allowing for unprecedented precision in reaching potential customers. However, with the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe, this seemingly boundless frontier faced new limitations. The retail industry, heavily dependent on the granular data offered by giants like Facebook, Google, and Snapchat, felt an immediate impact. Yet, surprisingly, while these tech behemoths were forced to change their strategies, car manufacturers emerged as the most flagrant violators of privacy norms.

Let’s take this from the beginning of the privacy movement.

GDPR and Early Implications

The primary objective of GDPR was to give European citizens more control over their personal data. Companies would now need explicit consent from users before harvesting their data. This posed a direct challenge to the advertising models of Facebook, Google, and Snapchat, which were hinged on the ability to collect vast amounts of personal data to deliver tailored ads. In a 2018 2PM report on the ramifications, I explained:

All roads lead to increased ad spend for retailers with Amazon at the behest of Google and Facebook. Amazon has a distinct advantage in so much that the entire commerce workflow can happen within their walls. We anticipate greater efficacy through Amazon’s channels. Especially considering that the United States will pass its own version of Europe’s GDPR Act within the next five years.

It’s been five years and I was wrong. America has yet to enact a federal law that directly parallels Europe’s. But state by state, stringent acts have been passed. And corporations like Apple have taken it upon themselves to enact privacy practices; 2PM has covered Apple’s post iOS 14.5 era extensively (parts (I-III linked here). Prior to this iOS change, retailers, who once enjoyed a rich influx of consumer data, enabled them to pinpoint advertising efforts efficiently. Since then, digital marketing has been a body of murky water. With platforms like Facebook having to limit data collection practices in compliance with Europe’s GDPR and Apple’s institution, the detail and depth of consumer insights available to retailers were diluted. The fine-grain targeting, which allowed companies to deliver ads to highly specific demographic segments, was curtailed, leading to what many in the industry perceived as a decline in advertising efficacy. A product’s ad that would have once seamlessly appeared in the feed of a consumer whose online behavior indicated interest in such products was now less likely to find its mark. The degradation of advertising accuracy was an unintended second-order effect of GDPR, but it was palpable.

Today, retail media has taken the place of the momentum builder that was Facebook and Google advertising. But there was a privacy oversight that I did not foresee.

The Automotive Industry: A Privacy Conundrum

While social media platforms and retailers were grappling with these new regulations, another industry was silently and rapidly morphing into a behemoth of data collection: the automotive industry. According to an investigation by Mozilla and follow-up reports by the Washington Post and Quartz, car manufacturers were collecting more data than ever before. These reports painted a grim picture, where the modern car was likened to a “computer on wheels,” gobbling vast amounts of data about its drivers and potentially all of its occupants.

Cars, with their sophisticated infotainment systems, sensors, and connectivity features, were capturing data ranging from driving patterns and destinations to personal conversations and even, alarmingly, indications of a driver’s sex life. Mozilla’s research found that every one of the 25 car brands they examined was collecting more data than deemed necessary. To add to the consumer’s woes, most car manufacturers were sharing, and in many cases selling, this data to third parties. Such extensive and intrusive data collection far outstripped even the most data-hungry social media platforms pre-GDPR. Here is the report card:

But why were car manufacturers not facing the same scrutiny and backlash as social media platforms? Part of the answer lies in the murkiness and complexity of data collection practices in the automotive industry. Unlike the relatively transparent (though still complex) practices of traditional consumer tech companies, car manufacturers have a more convoluted ecosystem of privacy policies that are challenging to decode. The operating systems are incredibly complex – with controls over a wider range of functions: technical, chemical, and mechanical. Furthermore, consumers often don’t view their vehicles as potential threats to their privacy, unlike their smartphones or computers. Automobiles are the ultimate trojan horse.

The introduction of GDPR, CCPA, and Apple’s privacy innovations have undoubtedly reshaped the digital landscape, particularly in the realms of advertising and data collection. While it forced a pivot for social media giants and retailers, leading to a decline in advertising precision, it also brought to light industries that were previously flying under the radar. The automotive industry, with its current trajectory, stands as a stark reminder that the fight for data privacy is far from over. As technological advancements continue to blur the lines between different sectors, it becomes paramount for regulatory bodies to stay vigilant, ensuring that all industries, irrespective of their nature, respect the privacy rights of consumers.

By Web Smith | Edited by Hilary Milnes with art by Alex Remy and Christina Williams