Beef is the most interesting topic in retail. By the end of this, you may agree.

Will Harris is the principal at White Oak Pastures. A fourth-generation cattlemen, Harris cultivates land and cattle that was passed down to him from descendants as far back as 1866. Educated at the University of Georgia, Harris was trained on industrial farming techniques that were popularized in the 1940s to feed a booming, middle-class economy. These methods include the typical pesticides, antibiotics, hormones, feed, and herbicides customary to American diets. Today, Will Harris is a regenerative cattle rancher whose detailed approach to farming is measured down to the microbe. I listened to a recent interview of his shared by a friend and cattle rancher. This soundbite has shaped the present and future of beef:

What you’re doing is fine, Will, but you can’t feed the world like that. And my response is, “I don’t know that I am supposed to feed the world, I think I’m supposed to feed my community.

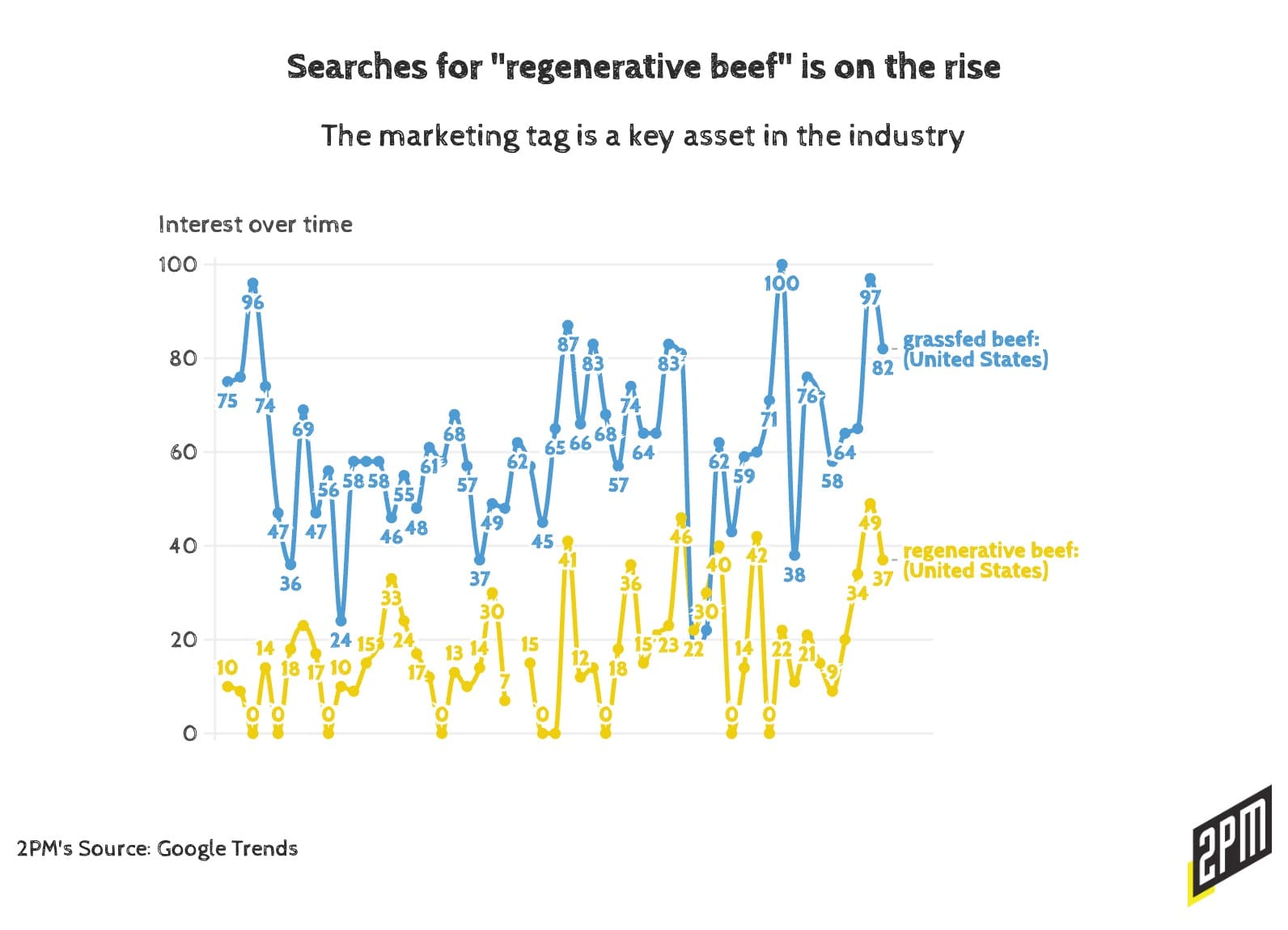

In recent years, the term “regenerative beef” has emerged as a popular marketing buzzword, heralded as a sustainable solution to environmental concerns associated with beef production. This essay examines the science and work that defines this word, one that has the potential to become a disingenuous marketing term, especially in light of the challenges the farming practice faces when scaled up.

This includes Walmart’s new initiative to redefine itself as a regenerative company; the economic realities of beef production and consumption, and the broader context of sustainable development all serve as critical lenses through which to understand this issue.

Started raising cattle at [the] Ko’olau ranch on Kauai, and my goal is to create some of the highest quality beef in the world.

These were the words of the owner of Ko’olau ranch, a 1,400-acre compound on Hawaii’s oldest island, according to a recent report by The Guardian. That property owner and modern rancher is Meta billionaire Mark Zuckerberg, who aims to raise the Rolls-Royce of beef.

Rolls-Royce manufactured 6,000 vehicles in 2022 up from 5,586 in 2021. In 2022, Ford manufactured 1.8 million vehicles. One car company manufactures for quality and the other manufactures for industrial scale. If this analogy was used for the production and marketing of beef, by the growing number of modern retailers, it would look something like this:

Over one dozen brands are vying for market share to be the Rolls-Royce of meat producers which requires production to look more like Ford’s, defying the ideals of the practices that established Rolls-Royce over decades.

The bottom line: there is only so much space in the regenerative meat market before it’s not regenerative at all. This means that companies should assume that the market is fixed and that expansion of supply either comes by degrading production or acquiring the supply of a competitor’s.

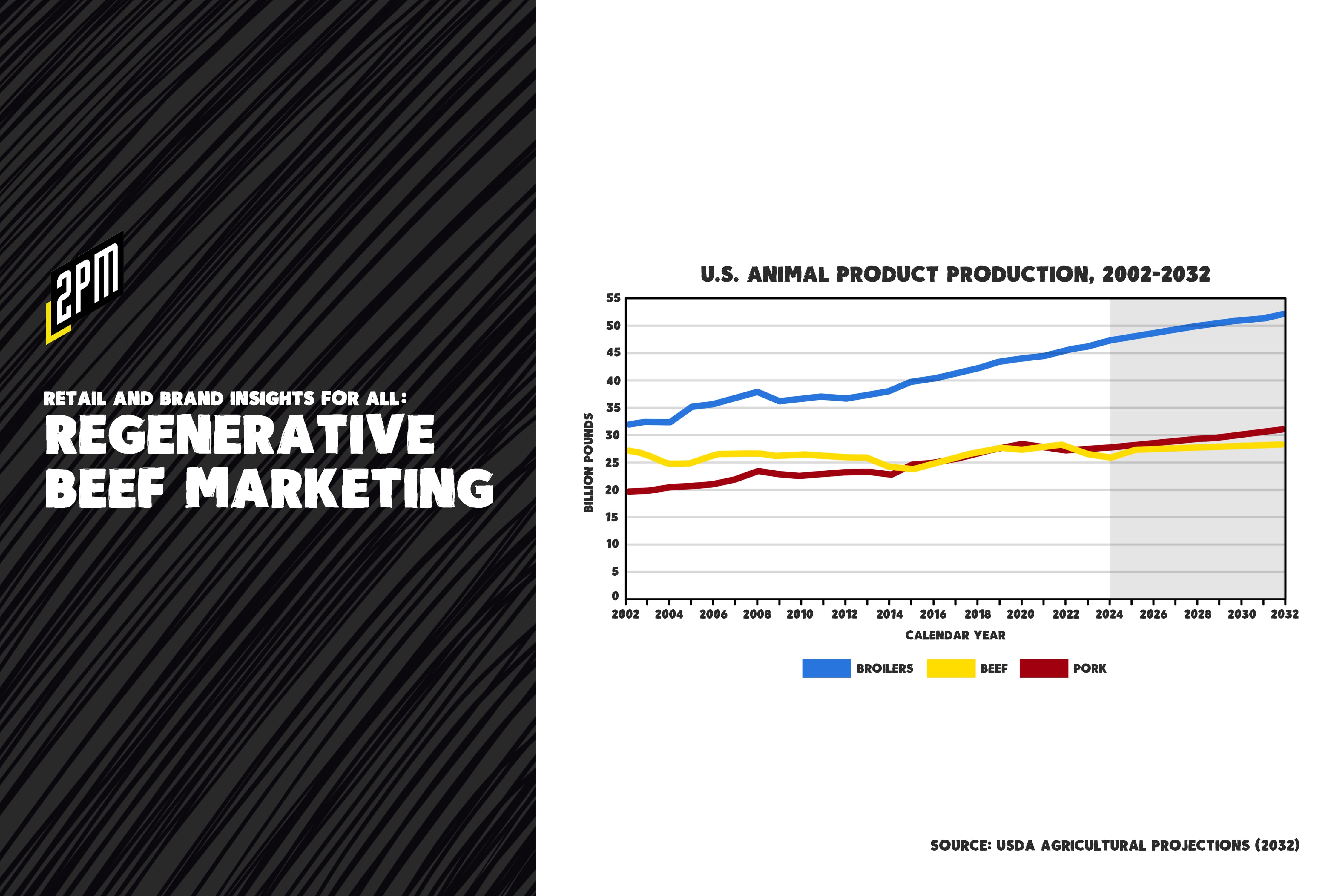

In short, there are now dozens of meat-based brands (across CPG and fresh foods categories) that are competing for market share in a segment where the supply is level, the demand is level, but the merchants are growing by the year. Look no further than the projection by the USDA, pictured above: chicken production will grow, pork production will inch up, beef production will remain the same.

Recent developments in both the traditional and alternative meat sectors suggest an ongoing struggle for market dominance, with each segment grappling with unique challenges. [Just Meat]

The use of the “regenerative” tag in beef production can be seen as a worthwhile initiative. The use of the tag in marketing is a form of virtue signaling, a term used to suggest that capitalism can be aligned with a corporation’s moral values, often with little regard to the totality of their impact. This use of the term can dilute its meaning and potentially mislead consumers about the environmental impact of their food choices.

Walmart’s Regenerative Foodscape

Here is a case in contradiction. Walmart, the world’s largest retailer, is now attempting to position itself as a leader in regenerative agriculture, despite the inherent contradictions with its low-cost business model. The Walton family, owners of Walmart, have made vast investments in regenerative agriculture. While these efforts might seem commendable, they potentially reshape the marketplace in a way that undercuts the true essence of regenerative practices. The Walton family’s influence over the food system, reflected in their substantial investments, does not align with the fundamental principles of regenerative agriculture, which prioritize environmental sustainability over profit and scale. Regenerative methods and capitalism rarely align. So for Walmart to attempt to own the narrative is especially concerning for those who are authentic about their duty to the regenerative agriculture movement.

It’s important to note that Walmart faced tension between two dueling concepts, once before: the organic produce market and its low-cost model. Organic produce economics and regenerative agriculture are systems with overlapping values, restrictions, and aspirations. As a foretelling of sorts, Walmart sells organic produce at a cost as much as “25% cheaper than any other grocer,” according to the company. From Walmart’s ‘Regenerative Foodscape’, a November 2023 report by Civil Eats:

Even if the Walmart fortune is truly creating a rising tide toward a more regenerative food system, it may be unlikely to lift the most battered of boats: those small, regenerative, diversified farms selling healthy food to their neighbors. Because at the end of the day, it costs more. And not only have they been losing money for years, they’re still caught in the everyday-low-price hurricane, trying to stay afloat within a system that rewards producers who scale up to sell at Walmart’s prices.

The expansion of Walmart’s grocery business, with its emphasis on low prices, has historically encouraged practices that are antithetical to regenerative agriculture’s ethos of ecological balance and sustainability. So the question becomes, if regenerative agriculture-based companies partner with Walmart – can they too be considered antithetical?

The Economic Realities of Beef Production

The beef industry’s economic landscape adds another layer of complexity to the notion of regenerative beef. Inflation in the beef sector, as noted by Haden Comstock of NCBA, has led to a decrease in beef availability per capita in America.

This reduction in supply, coupled with a rise in prices, highlights the challenges of transitioning to a truly regenerative model. Beef, as a protein source, has maintained its demand despite rising prices, but the economic pressures on consumers, especially those with diminishing savings, indicate a possible future shift in consumption patterns. The tension between maintaining affordability and adopting sustainable practices poses a significant challenge for the beef industry, particularly in the context of ongoing environmental changes like droughts in the Midwest.

Regenerative Agriculture: Promises and Limitations

A July 2023 whitepaper by the American Farmer’s Network stated the following:

By choosing grass-fed beef, individuals can contribute to a more sustainable food system, support local economies, and enjoy the health benefits associated with this responsible and mindful choice. As we move forward, it is crucial to prioritize the adoption of sustainable farming practices and raise awareness about the positive impact of grass-fed beef for a healthier and more sustainable future.

The concept of regenerative agriculture is rooted in practices that enhance soil health, biodiversity, and ecological balance. However, the applicability of these practices to larger-scaled regenerative beef industry remains questionable. Proponents argue that regenerative agriculture can mitigate climate change and improve environmental sustainability.

However, this optimism overlooks the inherent limitations of such practices when applied to cattle farming. Regenerative grazing, while marketed as a solution to environmental degradation, often requires significantly more land and may not effectively reduce greenhouse gas emissions or address biodiversity loss as a result of the lack of necessary land. From “The Promises and Pitfalls of Regenerative Agriculture, Explained,” a recent report by Sentient Media:

“Regenerative grazing” of cattle has been marketed to consumers […]. However, research shows that cattle grazing in any form is a major source of climate pollution that contributes to biodiversity loss, and regenerative ranching requires up to 2.5 times more land than conventional beef production.

The industrial-scale application of regenerative techniques faces challenges. The current trends in regenerative agriculture, driven by private funding (including by the Walton family) and government investment, risk perpetuating a model of agriculture that falls short of its environmental promises due to the changing priority from effectiveness to scale.

Brazilian President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva was recently quoted at COP28 in Dubai of all places:

We want to convince the people who invest in agriculture … that it is completely viable to keep the forest standing and (still) have land to plant whatever we want.”

There he detailed a plan to regrow 99 million acres of deforested land within the decade. – an area roughly the size of Sweden – within a decade. Context Magazine notes that this exceeds the landmass of Sweden. And it comes at a time when Brazil faces potential EU regulations banning commodities produced by acts of deforestation.

There are critics that suggest that regenerative agriculture, specifically beef production, would require far more land than we currently maintain for cattle raising. This is the simplest limitation but it isn’t the only one. While Mark Zuckerberg plans to use his 1,400 acre ranch to produce some of the world’s best beef, the masses will another 99 million acres over the next decade to keep supply at a place where the growing number of demand-generating DTC brands and other retailers in the space are taking the industry (assuming that the all grow with proper unit economics). This is why the regenerative tagline seems lofty at best, disingenuous at worst.

Regenerative Beef: A Marketing Ploy?

The labeling of beef as “regenerative” often serves more as a marketing strategy than a reflection of genuine sustainability. Hopdoddy, an Austin-based chain of fast-casual restaurants, just grew its vendor-partnership with Force of Nature – another Austin-based venture. Hopdoddy’s vice president of culinary Matt Schweitzer explained that part of the objective for switching meat vendors is to bring attention to regenerative agriculture:

We felt like we could really take a stand and look to move our entire supply chain in a regenerative fashion, so we could really be proud of the work we’ve done and we could hopefully leave the animals, the farmers, the ranchers, the native grasslands, and our planet a better place than before we started.

The term suggests a level of environmental stewardship that may not align with the realities of scaling beef production for mass-market ventures. This misalignment raises concerns about greenwashing, where the ecological benefits of regenerative practices are overstated to appeal to environmentally conscious consumers. The regenerative beef narrative may give the impression that consuming beef, regardless of its production method, is compatible with a sustainable food system. This perspective neglects the broader environmental implications of beef production. But more importantly, it fails to mention the limitations of supply.

****

The rise of “regenerative beef” as a marketing tagline represents a complex interplay between environmental aspirations and economic realities. While the concept of regenerative agriculture holds promise, its application to beef production at scale is fraught with challenges. Companies like Walmart, despite their investment in regenerative practices, operate within a framework that prioritizes scale and cost-efficiency, potentially undermining the principles of regenerative agriculture. The economic pressures on the beef industry, coupled with the need for environmental sustainability, call for a nuanced understanding of what regenerative practices can realistically achieve.

If the number of companies are growing and the strain on growers intensifies, is the corporate boom of direct-to-consumer meats true to its stated claims? As the global population grows and the demand for sustainable food systems only intensifies, it is important to look at this growing tagline with a critical eye and assess the claims of “regenerative meat” and the companies that rely on it to achieve scale.

By Web Smith | Edited by Hilary Milnes with art by Alex Remy and Christina Williams

Addendum: Organic searches

- “grassfed beef”: White Oak Pastures

- “grass fed beef” White Oak Pastures

- “grass-fed beef”: White Oak Pastures

- “regenerative beef”: Force of Nature

- “best beef DTC”: 6666 Ranch

- “beef box”: Seven Sons Farm

- “best meat DTC”: ButcherBox

- “ethical beef”: Seven Sons Farm

- “ethically sourced beef”: Seven Sons Farm

- “grass finished beef”: White Oak Pastures

- “american beef”: Snake River Farms

- “organic beef”: Organic Prairie

- “pasture raised beef”: Primal Pastures

- “regenerative meat”: Force of Nature

- “regenerative raised meat”: Force of Nature