On December 23, Oxford PhD and Stanford Economics Postdoc, Phillip Trammel, and Leopold Aschenbrenner published Existential Risk and Growth. The timing couldn’t be more relevant. We are living through a constant debate on the merits of subjective arguments across AI, policy, and technology circles: that slowing progress is the responsible thing to do when risk increases. Aschenbrenner’s independent work served as the basis for 2PM’s first NATSEC dispatch; it was, then, required reading. This, again, felt like required reading.

These authors are far more competent than the vast majority of us. Rare air is the capability to write as clearly as they; the gentlemen contended with ideas by establishing mathematical truths against them, setting a standard that most who’ve yet to encounter doctoral-levels of academia have yet to contend with. Every few years you come across a paper that forces you to quietly update a lot of assumptions you did not even realize you were carrying.

The main ideas they contend with appear in AI governance debates, in calls for innovation moratoria, and in the general belief that caution and delay are synonymous with wisdom.

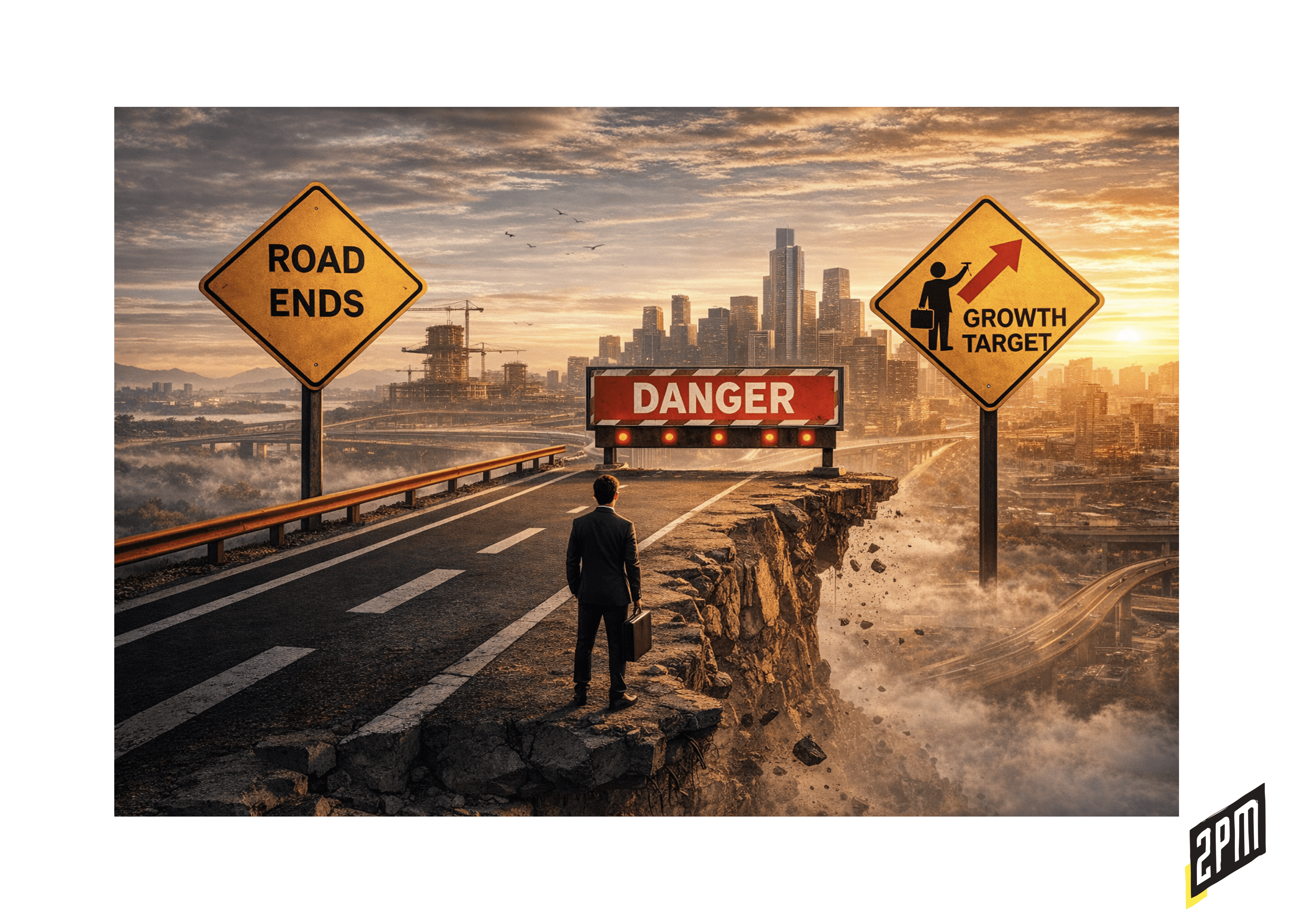

Stagnation is only safe if the current world is perfectly safe.

That instinct never fully squared with what I observe in markets, in business, and in human behavior. In eCommerce, in brand building, in infrastructure, and in national defense, the environments with the highest stakes are rarely stabilized by slowing down. They are stabilized by learning faster, building faster, and reaching the next structural equilibrium before your exposure compounds.

This paper finally gave that intuition a rigorous backbone. It does not argue from ideology or optimism; it argues from the mechanics of risk itself. Once danger exists, time becomes the most expensive variable in the system. Everything else follows from that.

The read is worth your time.

There is a recurring pattern in modern leadership that rarely gets interrogated with the seriousness it deserves. When confronted with volatility, institutional uncertainty, or technological acceleration that outpaces cultural digestion, executives reach for the same lever. They slow down, or they defer. They reduce exposure, or they wait for the environment to stabilize.

Permanent stagnation can lower transition risk by avoiding advanced experiments altogether, but an acceleration that only pulls forward their date leaves cumulative risk unchanged. If the hazard rate is strictly convex in the rate of experimentation, however, then faster growth increases transition risk. The tradeoff between lowering state risk and raising transition risk can render the risk-minimizing growth rate finite, but as long as there is any state risk at all, it remains positive. [Page 4]

This reflex is nearly universal. It is also structurally misguided.

The most consequential insight in recent thinking on existential risk is not that technology is dangerous. Rather, it is that time itself becomes dangerous the moment risk exists at all. Once the probability of catastrophic failure rises above zero, every additional unit of time spent inside the current system increases total exposure to failure. The world is already in that condition.

- Nuclear weapons exist.

- Pandemic capability exists.

- Bioengineering exists.

- Climate dynamics exist.

In this way, we truly are beyond the neutral baseline (even if we choose to ignore it). There is only a hazard rate, a probability that the heightened baseline becomes more noticable. And the mathematics of hazard produce a conclusion that directly contradicts the dominant narrative of precaution: if danger already exists, slowing technological progress usually increases the total probability of civilizational failure.

This is not rhetoric; it is structural logic.

Time Is the Hidden Variable of Risk

Risk is not simply about what might happen. It is about how long you remain in a state where something might happen. If the probability of collapse in any given year is non-zero, then long-run survival depends on whether the cumulative risk remains finite. That depends not on how careful you feel, but on how quickly you can move beyond dangerous conditions.

This produces an uncomfortable truth. Stagnation is only safe if the current world is perfectly safe. It is not. Freezing progress while danger exists does not stabilize the system. It mathematically guarantees eventual catastrophe. Waiting does not eliminate risk. It compounds it.

Stagnation is safe, as assumed in existing literature, only if the current technology state poses no such risks. [Page 27]

This insight alone dismantles much of the contemporary obsession with technological pause. Pausing does not reduce danger when danger is already embedded; it merely increases exposure time.

Innovation Does Create Risk and That Still Does Not Save the Slowdown Argument

The standard objection is that innovation itself is dangerous: experiments fail, systems break, deployment creates new vulnerabilities. All of this is true but the conclusion drawn from it is usually wrong.

When making tradeoffs over time, it is uncontroversial to discount later periods for reasons of uncertainty. [Page 32]

Even when experimentation introduces new hazards, slower progress only becomes safer under extremely narrow conditions. As long as any background danger exists, the growth rate that minimizes risk remains positive. Zero growth is never the safe option once risk is already in the system. The real strategic error is confusing short-term volatility with long-term safety.

The Economics of Safety

The most underappreciated part of this framework is economic, not technological. As societies grow wealthier, the value of life rises. The marginal value of additional consumption falls, and the willingness to sacrifice output for safety increases dramatically. Growth does not simply produce new dangers. It manufactures the political, institutional, and financial capacity to neutralize them.

At first, things get worse:

- Pollution rises.

- Inequality rises.

- Cities get messy.

- Labor conditions deteriorate.

- The side effects of growth show up everywhere.

But after a certain point, something flips. Once people are wealthy enough, they start caring more about clean air, worker safety, health, education, and the long-term quality of life. They can finally afford to fix the problems growth created. So the curve looks more like an upside-down U:

- Early growth: more wealth, more problems

- Later growth: more wealth, fewer problems

- Growth causes the mess, then growth pays to clean it up.

That is the Kuznets Curve. This creates a structural pattern that mirrors the environmental version of the curve. Risk may rise early in development, but accelerating growth eventually generates the resources and incentives for aggressive safety investment, which sharply reduces hazard rates.

In other words, growth builds its own seatbelts. When policymakers and institutions respond rationally, acceleration reduces risk twice. It shortens exposure to dangerous states and it pulls forward the arrival of high-safety regimes.

What Executives Miss and Why It Matters

This is not an abstract debate about civilization. It is a leadership problem. I see this pattern constantly in eCommerce, brand development, and consumer psychology. When markets destabilize, executives freeze. They cut product, they pause launches or worse, they fail to invest in digital channels. They reduce experimentation; they wait for clarity. What they actually do is extend their exposure to the very uncertainty they are trying to escape.

Risk is not eliminated by waiting. It is outrun.

The brands that survive disruption do the opposite. They accelerate through it. They ship faster or they learn faster. They adapt faster and they reach stable ground first.

Specific industries have internalized this logic completely. Defense technology never pauses. When the threat increases, acceleration becomes the strategy. Data infrastructure behaves the same way: rising complexity demands faster buildout, not slower. Entertainment follows the same pattern. Fragmented attention requires aggressive output, not restraint.

These sectors understand what most executives resist admitting: risk is not eliminated by waiting. It is outrun.

The Strategic Reframe

What every executive should take from this work is simple and deeply uncomfortable. Slowing down feels safe because it reduces short-term stress. It does not reduce long-term risk. When danger exists, speed is the only instrument that compresses exposure. Caution must be expressed in steering and reinforcement, not in braking.

Civilization is not standing at the edge of a cliff; it is already falling. The only direction that reduces impact is forward.

More on Stanford’s Digital Economy Lab. More on Situational Awareness.