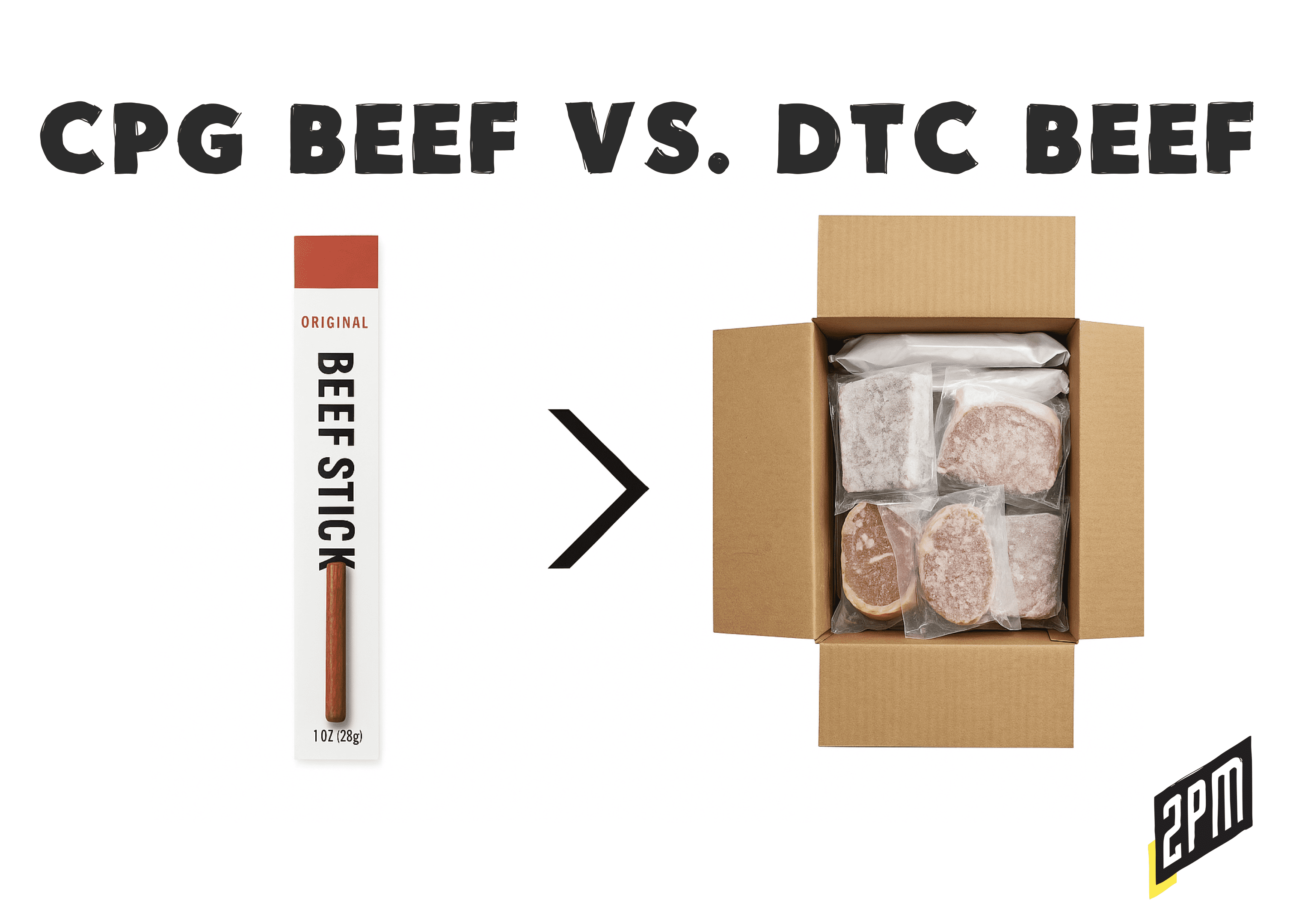

A funny thing happened while direct-to-consumer meat hit a ceiling: the humble beef stick escaped the snack aisle. In 2024, Circana estimated that U.S. dried meat snacks, excluding jerky, generated roughly $3.3 billion in 2024, up more than ten percent from the year before, and the “stick” format is driving most of that growth. Since 2020, the category has added more than a billion dollars in retail sales. It’s the kind of expansion curve DTC founders used to dream about before freight bills and cold-chain math woke them up.

The same period has been merciless to online beef. Herd sizes in the United States have fallen to their lowest level since the early 1950s, pushing cattle prices to record highs. The USDA’s boxed-beef reports confirm a stubborn elevation in cutout values, and parcel carriers keep tacking on surcharges for insulated packaging and dimensional weight. In other words, it doesn’t matter how refined your subscription interface is—every order leaves the warehouse heavier, costlier, and more fragile than the last.

The stick lives on the other side of that cost curve. It’s shelf-stable, light, and high-protein, and it no longer feels like a gas-station impulse buy. Circana’s latest data places total U.S. meat-snack sales at about $5.5 billion for the year ending October 6, 2024, with beef sticks as the fastest-growing segment that went into 2025. Where frozen beef boxes are bound by physics and packaging, sticks are bounded only by convenience-store shelf space.

Mapping the field

To understand why this subcategory feels limitless, it helps to map the field.

At the top is Link Snacks, the privately held company behind Jack Link’s. It remains the category leader by jerky dollars; roughly $889 million in the most recent 52-week reading—and its sticks portfolio benefits from the same scale. Link’s sourcing is largely domestic, supported by massive owned manufacturing infrastructure that few can match.

| Rank | Brand / Parent | Est. 2024 Revenue | Primary Sourcing | Channel Focus | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jack Link’s (Link Snacks) | ~$889M (jerky dollars) | U.S. & global | Mass retail, club, convenience | Category leader; owns manufacturing |

| 2 | Conagra (Slim Jim, Duke’s) | ~$3.2B snacks division | U.S. blended proteins | Mass retail, C-store | Heritage leader in sticks; expanding “Bites” format |

| 5 | Country Archer | $151–200M | 100% grass-fed U.S./LatAm | Grocery, club, online | Regenerative sourcing; 36% YoY growth |

| 6 | Johnsonville (Vermont Smoke & Cure) | n/a | U.S. | National grocery | Johnsonville acquisition; scale expansion |

| 7 | Tillamook / Old Wisconsin / Werner / Oberto | Regional (~$50–100M each) | U.S. + mixed imports | Grocery, C-store | Long-tail players |

| 8 | Western Smokehouse Partners | Co-mfg capacity target: 1.1B sticks | U.S. | Contract manufacturing | $500M valuation |

| 9 | Monogram Foods | n/a | U.S. | Private-label + licensing | Produces for Butterball & others |

| 4 | Old Trapper | ~$365M | U.S. + Australia | National retail | Family-owned, fast growth |

| 3 | Chomps | ~$500M (est.) | 90% Australia (Tasmania/Victoria) | DTC + retail (180k doors) | Clean-label insurgent; 525M sticks sold in 2024 |

Conagra follows as the institutional incumbent. Slim Jim, now more than a century old, still anchors Conagra’s $3.2 billion snacks division. The brand’s ingredient list blends beef, pork, and chicken, all made in the United States, and its growth has come through snack-size innovations like Slim Jim Bites, one of the fastest-moving formats in the aisle. Duke’s, the craft-positioned label under the same corporate roof, adds a touch of premium legitimacy.

Old Trapper, based in Oregon and still family-owned, has become the quiet second-largest jerky name in the country with an estimated $365 million in annual retail sales. Customs data show imports from Australia supplementing U.S. beef supply, an increasingly common hedge against domestic price volatility.

Country Archer sits at the next rung. The company, operating under S&E Gourmet Cuts, reported $126.8 million in jerky dollars in 2024, up thirty-six percent year over year. Press estimates place total revenue somewhere between $150 million and $200 million. Every bag and stick touts “100 percent grass-fed and finished” beef and a commitment to regenerative agriculture partnerships.

Then comes the insurgent: Chomps.

By founder accounts and trade-press tallies, Chomps sold more than half a billion sticks in 2024, approaching $500 million in gross revenue. Distribution now spans roughly 180,000 retail doors. About ninety percent of its beef comes from Australia—specifically Tasmania and Victoria’s Cape Grim region—while turkey is sourced domestically and venison from New Zealand. The products are manufactured and distributed in the United States. In less than a decade, the brand turned clean-label protein into a mainstream habit.

Johnsonville, through its Vermont Smoke & Cure subsidiary, is pushing national after an acquisition that gave the sausage giant a foothold in premium sticks. Tillamook Country Smoker, Old Wisconsin (owned by Buddig), Werner, and Oberto under Premium Brands each maintain regional or national positions with mixed sourcing and co-manufacturing. Behind the scenes, contract manufacturers are scaling at astonishing rates. Western Smokehouse Partners, for example, was valued near $500 million and plans to produce 1.1 billion sticks annually by 2026. Monogram Foods, another private-label powerhouse, runs licensed lines for names like Butterball.

If you rank them by available public signals, the hierarchy looks something like this: Jack Link’s first by a wide margin; Conagra’s Slim Jim and Duke’s next; Old Trapper third; Chomps close behind as the pure-play growth engine; Country Archer as the rising premium competitor; and Johnsonville’s Vermont Smoke & Cure rounding out the national tier before a long tail of regional makers. Each depends on a mix of U.S. and Australian supply, but the sourcing story—who buys from where—has become a brand differentiator in itself.

Their initial concept was different from what Chomps became. Originally, they considered selling frozen, grass-fed beef directly to consumers, but the challenges of shipping frozen meat quickly became apparent. To simplify logistics and make the product more accessible, they pivoted to shelf-stable, individually wrapped meat sticks which would define the future of Chomps and the meat snack category itself.

Introduction: The Snack that Outsmarted the Brand

In 1994, Slim Jim was untouchable. Jeff Slater, then VP of Marketing at GoodMark Foods, recalls the swagger of the era: billion-unit annual production, Macho Man Randy Savage screaming through television sets, and $250 million in sales that made the brand synonymous with shelf-stable protein. “We thought we owned portable protein,” Slater wrote years later. And for a time, they did.

When ConAgra acquired Slim Jim, it inherited a juggernaut that produced over a billion sticks a year across more than twenty varieties. Even today, industry observers estimate that Slim Jim’s annual revenue sits between $600 million and $800 million—a brand that never truly left the convenience store checkout. Yet beneath the familiar snap, the foundation was softening. By the mid-2010s, consumers were no longer entertained by preservatives they couldn’t pronounce or “mechanically separated chicken.” They were reading ingredient labels.

That’s when two outsiders, Pete Maldonado and Rashid Ali, did what legacy CPG couldn’t. With a $6,500 investment and a paleo grocery list, they reverse-engineered the industry from the bottom up. Their company, Chomps, began as a mail-order service, pivoted into individually wrapped sticks, and became the fastest-growing brand in protein snacking—producing two million sticks a day and approaching half a billion dollars in annual sales.

Slater’s retrospective tells the story simply:

Chomps didn’t try to out–Slim Jim Slim Jim. They became the anti–Slim Jim.

It was less a rebellion than an evolution—the same format, reborn under new rules. Slim Jim had marketed attitude; Chomps marketed intention. One chased cost efficiency and mass-market appeal; the other built loyalty through clean labels, sustainable sourcing, and Whole30 certification. One doubled down on volume; the other scaled through trust.fwhy one

The irony is that both brands sell the same idea: convenient protein you can eat with one hand. But only one speaks the new consumer language of health, transparency, and performance. Slim Jim once promised fun; Chomps promises function.

That divergence, the old guard’s fixation on distribution and the upstart’s obsession with alignment, sets the stage for a larger story about American protein commerce. The direct-to-consumer beef industry, for all its innovation, is capped by physics: rising cattle prices, cold-chain costs, and shipping fees that erode contribution margin before the first bite. The beef-stick industry, by contrast, feels like it has no ceiling. It is cheap to move, easy to store, and endlessly expandable across retail, convenience, and on-the-go channels.

This is not merely a case of small defeating large. It’s an object lesson in how consumer priorities: health, portability, identity can reroute entire supply chains. In 2025, while DTC beef battles volatility, the stick has quietly become the most scalable protein format in America.

From here, the story unfolds beyond nostalgia. It’s a map of a category once defined by a single brand that now belongs to a movement.

Why one ceiling and one sky

Direct-to-consumer beef, by contrast, has been bound by logistics and commodity cycles. Upstream inflation starts with the animal. With U.S. cattle inventories at seventy-year lows, processors pay more for every carcass, and ranchers hesitate to expand herds in a drought-stressed climate. The wholesale cutout values, the prices packers receive for boxed beef, remain high. Add in freight: every twelve to twenty-pound frozen assortment shipped to a customer carries the weight of gel packs, insulation, and hazmat-compliant dry ice. Major carriers treat those boxes as oversized, and each “additional-handling” surcharge erodes contribution margin. Even with strong average order values, the unit economics tilt against the operator.

| Metric | DTC Beef Box (12–20 lbs) | Beef Stick 12-Pack |

|---|---|---|

| Product Weight | ~18 lbs (incl. gel packs, insulation) | <1 lb |

| Shipping Type | Cold chain / dry ice | Ambient parcel |

| Average Freight Cost | $18–$26 per order | <$4 per order |

| Retail Price / Order | $140–$220 | $24–$36 |

| Contribution Margin | 20–25% (volatile) | 45–55% (stable) |

| Spoilage / Returns | 3–5% | <0.5% |

| Channels | Subscription, DTC only | Retail, C-store, Amazon, gym, travel |

| CAC Recovery | 3–4 orders | Immediate (impulse sale) |

| Shelf Life | 5–7 days in transit, frozen 6 mo. | 12+ months ambient |

| Repeat Behavior | Subscription churn risk | On-the-go repeat impulse |

The business model that looked brilliant when fuel was cheap and cattle abundant becomes brittle under the weight of inflation. Consumers, meanwhile, are less loyal to meat subscriptions than to coffee or supplements; a single bad delivery or price swing can prompt a pause or cancellation. The ceiling for DTC beef is not theoretical, it’s practical. And it’s already visible.

Beef sticks flip that equation. Ambient shelf life removes the cold-chain constraint. A twelve-pack ships for the cost of a book, not a cooler. The same product can sit in convenience stores, gyms, airports, or Amazon warehouses. The channel optionality is enormous: convenience stores are, in a sense, the second internet—hundreds of thousands of points of distribution that reward fast velocity rather than high margins.

The format itself keeps evolving. Bite-size sticks, mini packs, and flavor assortments create repeat purchase behavior without discounting. Conagra credited those small-format innovations for Slim Jim’s sustained growth. Co-manufacturers are adding capacity by the hundreds of millions of units, anticipating that stick demand will double again within two years.

And the consumer psychology has changed. The pandemic normalized protein snacking, while the GLP-1 conversation made portion-controlled, sugar-free options fashionable. A beef stick now signals health and discipline rather than convenience and guilt. It is a tidy fit for high-protein, low-carb, or intermittent-fasting lifestyles—the kind of cross-category relevance that DTC beef boxes can’t replicate.

The economics of freedom

The comparison is blunt but instructive. Direct-to-consumer beef sits atop a pile of volatile inputs: cattle costs, feed costs, fuel, labor, packaging, and last-mile delivery. Each layer compounds the risk. Even brands that control their own processing facilities struggle to pass through price increases fast enough. The category rewards vertical integration and regional micro-fulfillment, but few can afford the infrastructure.

Beef sticks, on the other hand, operate in an environment of relative stability. The product’s logistics are ambient, the margins healthier, and the distribution mix diverse enough to weather inflation. When Circana reports that meat sticks grew more than ten percent in 2024 while the broader snacks market crept upward only modestly, it underscores the point: this is one of the few packaged-protein formats with genuine runway left.

For founders and investors, the lesson is not to abandon beef but to rethink the hierarchy of SKUs. Treat the cold-chain operation as the hero product, the showcase for brand integrity, but finance it with shelf-stable formats that can move everywhere. Of course, this requires a Chief Marketer with decision-making autonomy. This is difficult to find.

Every successful meat company in 2026 will be a hybrid—part fresh, part ambient, part omnichannel.

The co-manufacturing arms race reinforces that thesis. Western Smokehouse’s billion-stick target is not just capacity, it’s a vote of confidence in long-term demand. Monogram’s quiet dominance in private-label licensing hints that large food conglomerates view sticks as their next billion-dollar bolt-on. As Western and others scale, the barrier to entry falls for brands with strong identities but no plants of their own. The next generation of premium meat brands will likely be born from this outsourced ecosystem, not from ranchland.

A market without a ceiling

The American DTC beef industry has met its upper limit. Rising input costs and shipping economics ensure that its growth curve will flatten until a logistics breakthrough arrives. The beef-stick industry, meanwhile, is only now hitting its stride. With double-digit growth, billions in new capacity, and mainstream cultural acceptance, it’s becoming the rare protein business that feels uncapped.

Where one side of the market is weighed down by insulation and ice, the other fits in your pocket. And in commerce, weight still matters.

Research and Writing by Web Smith