Los mercados públicos actuales parecen penalizar los cultos a la personalidad. Para ver un ejemplo, basta con echar un vistazo a la debacle actual de WeWork. En una secuencia de acontecimientos que puede recordar a la destitución del fundador y consejero delegado de Uber, WeWork también obtuvo capital riesgo de Softbank y Benchmark. Y resulta que el consejo de la empresa está en desacuerdo con su propio fundador y CEO, justo a tiempo para una oferta pública inicial largamente esperada.

Es sorprendente lo rápido que Adam Neumann se ha convertido en un paria. Siempre he pensado que el negocio tenía un valor cuestionable. Pero va a mostrar cómo muchas personas son "resultado sobre el proceso". Y el segundo la oferta pública inicial tropieza, los cuchillos salen.

Nick O'Brien

Dos empresas respaldadas por capital riesgo con pérdidas crecientes y caminos cuestionables hacia la rentabilidad, y sólo una de ellas parece superar el listón de la salida a bolsa. Una de ellas rinde culto a la personalidad de Adam Nuemann, la otra a la forma física gracias a consumidores como usted. Peloton, un sector notoriamente voluble, ha combatido los altibajos de las microtendencias del fitness contratando y reteniendo a los mejores directivos. Para Peloton, la retención es el KPI.

Dirigida por John Foley, Peloton es a partes iguales: calidad del producto, calidad de la programación y calidad de sus usuarios. Estos usuarios son el factor x colectivo de Foley. También es una cohorte más vulnerable de lo que se piensa.

Peloton reportó un impresionante ingreso total de $ 915 millones para el año que finalizó el 30 de junio de 2019, un aumento del 110% desde $ 435 millones en el año fiscal 2018 y $ 218,6 millones en 2017. Sus pérdidas, mientras tanto, alcanzaron los 245,7 millones de dólares en 2019, un aumento significativo desde una pérdida neta reportada de 47,9 millones de dólares el año pasado.[1]

A medida que se acerca la salida a bolsa de Peloton, la empresa ha optado por experimentar con una nueva promoción de ventas. La expectativa es que Peloton refuerce algunas métricas clave: nuevos usuarios, nuevas suscripciones y número de flujos. Al instituir la "garantía de 30 días" que se encuentra en productos informales de fitness como NordicTrack y Bowflex, Peloton corre el riesgo de reducir el valor de la vida útil (LTV), aumentar la rotación y condenar al ostracismo a la base altamente motivada de la empresa mediante la comercialización a los usuarios ocasionales y bajando de mercado.

Al principio, los compradores de Peloton debían adquirir el equipo en su totalidad. Al asociarse con Affirm, la startup de financiación al consumo, la empresa de hardware y software abrió las puertas a la financiación al 0% en 36-48 meses. Esto abrió el producto a los consumidores de clase media sin degradar el LTV y el valor medio del pedido. Esta semana, la empresa ha dado un último paso para reducir las fricciones. Pero mientras los analistas alaban la medida como un factor de crecimiento, yo diría que puede ser contraproducente.

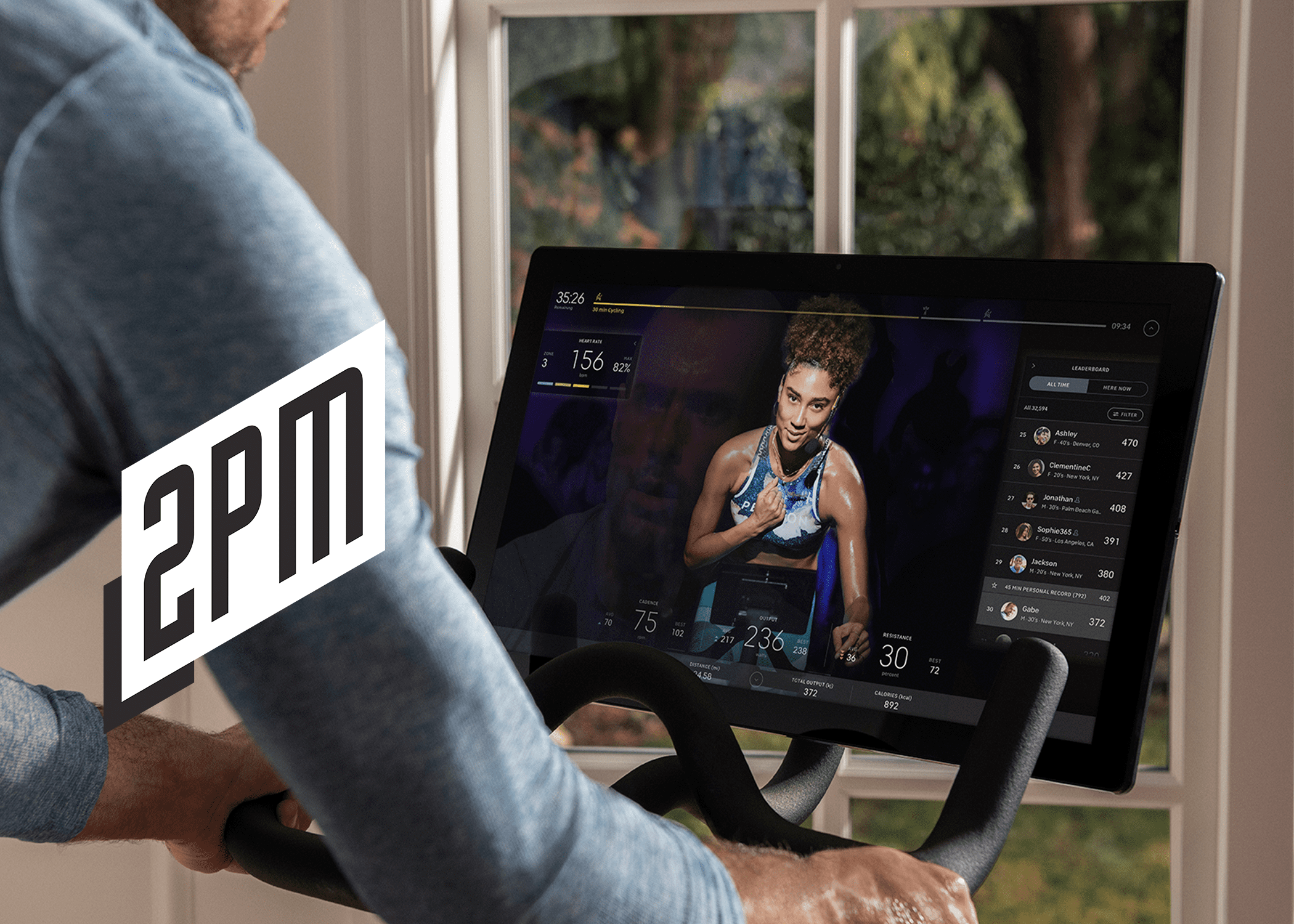

Peloton no se parece a nada que hayamos visto antes. Para los usuarios avanzados, la bicicleta negra mate se ha convertido en una fuente de inspiración, motivación e incluso responsabilidad. Personalidades como Ally Love y Alex Toussaint se han convertido en nombres conocidos. Este mismo verano, la leyenda del tenis Chris Evert hizo notar su aprecio por Ally Love durante la retransmisión del US Open de tenis. Señaló que Love era "su instructora de spinning". Antes de ese momento, nunca se habían conocido en persona. En mi propia casa, de vez en cuando le pregunto a mi mujer sobre sus sesiones de entrenamiento: "¿Qué tal Alex, hoy?". Se ríe cada vez; la "broma" entre nosotros es que se niega a entrenar con otro instructor.

El culto a Peloton no está anclado en el equipamiento. Más bien, son los recursos humanos de la empresa los que siguen atrayendo. Y, sorprendentemente, la empresa parece dispuesta a manipularlo para crecer a corto plazo.

A partir de la presentación en junio del S-1 de la empresa, Peloton contaba con más de 511.000 abonados y casi 85 millones de sesiones acumuladas. Para muchos usuarios, es una especie de adicción. Pero la adicción no se debe tanto al producto físico como a su eficacia. Eso tarda en materializarse, mucho más de un mes. El volante de marketing de la empresa de hardware se perpetúa gracias a los consumidores que lo evangelizan. Yo diría que el horizonte temporal para comprender su valor está más cerca de los tres meses. Un mes de prueba parece un motor de rotación, no un embudo de adquisición.

A partir de la presentación en junio del S-1 de la empresa, Peloton contaba con más de 511.000 abonados y casi 85 millones de sesiones acumuladas. Para muchos usuarios, es una especie de adicción. Pero la adicción no se debe tanto al producto físico como a su eficacia. Eso tarda en materializarse, mucho más de un mes. El volante de marketing de la empresa de hardware se perpetúa gracias a los consumidores que lo evangelizan. Yo diría que el horizonte temporal para comprender su valor está más cerca de los tres meses. Un mes de prueba parece un motor de rotación, no un embudo de adquisición.

He vendido una Peloton a varios colegas. Esto es habitual, el S-1 sugiere un alto índice de ventas boca a boca. Al vender el producto a mis colegas, he observado que los trayectos son dolorosos, pero que merece la pena. El hardware es precioso y la transmisión en directo aumentada es extraordinaria. Pero es la sensación de logro y el compromiso con la plataforma lo que me ha parecido más valioso para el valor de marca del producto. Así que sí, parte de la fidelidad proviene del compromiso con la propiedad.

Comprender las estrategias de dualización en la industria del fitness:

- Planet Fitness prospera gracias a una baja motivación, un compromiso a corto plazo, una fidelización relativamente mínima y un bajo nivel de deserción. Los costes son tan bajos que muchos socios se olvidan de que están pagando. Esto es así por diseño. Los costes son mínimos porque el volumen es la clave. Si todos los socios acudieran el mismo día, no habría espacio para hacer ejercicio. Planet Fitness es un modelo de gimnasio.

- Equinox se nutre de una alta motivación, efectos de red, compromiso a largo plazo y bajo desgaste. Los costes son relativamente elevados, pero evitan la masificación y financian los servicios. La red y los servicios hacen que los clientes vuelvan. Equinox es un modelo de club.

En el apogeo de la moda del fitness funcional, el crecimiento de CrossFit se vio impulsado por la alta participación, la eficacia y el evangelismo entre iguales. Los clientes de los gimnasios tradicionales pagaban un suplemento por inscribirse en uno de los 7.000 garajes y almacenes de todo el mundo. Estos clientes buscaban un disfrute retorcido de entrenamientos desafiantes (y la transformación física posterior). Pero, lo que es más importante, buscaban una comunidad activa. Peloton está pasando de la exclusividad del modelo de club a la inclusividad del modelo de gimnasio. Y aquí es donde las cosas se complican para Peloton. La nueva estrategia de precios entra en conflicto con la viabilidad a largo plazo de su posición en el mercado.

No pasa nada en un mes

La promoción de 30 días de prueba ha sido ampliamente difundida en publicaciones como Bicycling Magazine y Shape.

Esta nueva oferta es una forma inteligente de que la marca ofrezca a los clientes potenciales a largo plazo una verdadera experiencia de la bicicleta y la amplia variedad de clases de entrenamiento. Para ti, es una forma estupenda de probar antes de comprar.[2]

Este mensaje entra en conflicto con muchas de sus propuestas de valor. Si tuviera que adivinar, probablemente fuera un punto de conflicto dentro de la cúpula directiva. La estructura corporativa de la empresa es única. Tiene nueve miembros en esa c-suite. Sin embargo, un jefe de marketing (CMO) no es uno de ellos. Es un ejemplo de una tendencia desafortunada en el sector minorista de consumo. Después de tres años como directora senior de marca de PepsiCo, Carolyn Blodgett dejó una breve etapa en la organización de los New York Giants para convertirse en la directora senior de marketing de Peloton. Como SVP, es probable que dependa del Chief Revenue Officer (Tim Shannehan) o del Chief Content Officer (Jennifer Cotter).

De este modo, la falta de una visión singular puede desempeñar un papel en la decisión de Peloton de probar un sistema de prueba. Aunque los incentivos de precios no son raros en las ventas de SaaS o en la comercialización de bienes físicos, suelen ser la punta de lanza de las marcas que buscan introducir más descuentos e incentivos. Y suponen un problema para una empresa que se definirá en gran medida por las mejores prácticas de los gimnasios y los efectos de red basados en software. Peloton tendrá dificultades para explicar la supremacía de su producto cuando los periodos de prueba pasen de un mes a tres o cuatro. O peor aún, cuando el ciclo de 2.300 dólares que usted pagó esté a la venta por 1.200 dólares durante la temporada de vacaciones. Los incentivos de precios son un terreno resbaladizo.

Con los costes de marketing e inmobiliarios comiéndose la rentabilidad neta de Peloton, la escritura está en la pared. La empresa cree que los costes de crecimiento se han encarecido demasiado y, con una OPV de 1.200 millones de dólares a la espera, la historia del crecimiento eficiente puede determinar la viabilidad de la empresa en los próximos dos trimestres. Por desgracia, puede tratarse de una inyección de crecimiento con poca visión de futuro.

Al igual que el intento de WeWork de silenciar su culto a la personalidad, Peloton corre el riesgo de debilitar su culto a la forma física. Sólo uno de ellos parece intencionado. No está claro si la dirección de Peloton comprende plenamente los riesgos que entraña. La fuerza de la empresa tiene dos vertientes: su talento en pantalla y su culto a los primeros usuarios. Puede que el mercado recompense a Peloton por apostar por nuevos métodos de influencia y captación. Sin embargo, sus directivos no empezarán a ver los efectos no deseados de la adopción masiva (y el aumento de la rotación) hasta que su volante de marketing empiece a mancharse.

En el desafortunado caso de que eso ocurra, Peloton se convertirá en otra bicicleta doméstica con pantalla. Y en ese caso, los consumidores verán mucho más las palabras Peloton Infomercial 20:00 en la parrilla de su guía de cable. Y ese no es lugar para vender una religión.

Lea aquí la curación del nº 332.

Informe de Web Smith | About 2PM

Lectura adicional: Peloton vs. Tonal (Investigación de los miembros)

This is a weak argument at best.

One of their investors suggested that my analyses were sound. Which part bugged you?

[…] effects of mass adoption (and increased churn) until its early marketing flywheel begins to sully. [7] But for many of Peloton’s early adopters, they see cracks in the anemoia that benefited the […]

[…] Previous Post No. 332: Risk and Religion of PelotonNext Post No. 333: Food52 and Linear Commerce […]