Tim Armstrong no se equivoca. DTX " en DTX Company es la abreviatura de "Direct to Everything" (Directo a todo); el fondo espera aportar una chispa proverbial a esta era del comercio minorista en línea. Tim Armstrong, antiguo Consejero Delegado de Oath, anunció el lanzamiento de su última empresa con la siguiente declaración de intenciones:

Invertimos en fundadores impulsados por su misión que son líderes en la economía de marca directa. Estamos construyendo la infraestructura para la economía de marca directa mediante la creación de experiencias, el diseño de plataformas y la inversión en fundadores y talento. [1]

DTX es en parte un fondo de riesgo y en parte un amplificador de marcas DTC. El fondo ya ha invertido en seis empresas nativas digitales bien establecidas, con una tesis de inversión centrada en su atractivo para los influyentes consumidores millennials de DTC. Volveré sobre la importancia de la influencia al final.

El 6 de noviembre, su empresa DTX se puso en contacto con 120 marcas de venta directa al consumidor, haciéndoles la invitación de unirse a DTX como socios oficiales en el DTC Friday inaugural, el último evento de venta al por menor hecho por el hombre. Armstrong se une así a Jack Ma y Jeff Bezos. El evento, de un día de duración, contó con la participación de las empresas de la cartera de DTX y unas 110 más que Armstrong reclutó. Apenas siete días después, se anunció la jornada y, el viernes siguiente, el antiguo CEOde Oath acudió a la CNBC para explicar su visión de las marcas nativas digitales.

Se trata realmente de tener una alternativa a las plataformas [FAANG]. [...] Queremos trasladarlo todo a los bordes.

La promesa del evento era sencilla: DTX se anunciaría ante 150 millones de consumidores potenciales. Sin embargo, no funcionó para muchas de las marcas asociadas. Fred Perrotta, de mochilas Tortuga, informó:

Desde las 10 de la mañana hora del Pacífico, dtcfriday.com nos ha enviado 14 visitantes, casi tantos como Duck Duck Go.Tuvimos mejores resultados cuando Bitcoin Black Friday todavía estaba activo.

Dirigida por el cofundador y CEO Matt Bahr, Enquire es una empresa SaaS que realiza encuestas de atribución para cientos de tiendas Shopify. La plataforma de Bahr trabaja con 15 de las 120 marcas que se asociaron con DTX Company. En total, esas marcas obtuvieron diez ventas atribuidas a los esfuerzos de DTX Company.

Analizamos datos anónimos de respuestas a encuestas y parámetros UTM de las marcas de DTC Friday con las que trabajamos. Varias de ellas se destacaban en el sitio web de DTC Friday y descubrimos que menos de una docena de pedidos se atribuían a la campaña. Desde nuestra experiencia trabajando con marcas directas al consumidor, esto no es demasiado sorprendente. El enfoque generalizado de los medios de comunicación no suele ser eficaz para impulsar las conversiones en periodos de tiempo tan cortos.

Nik Sharma, uno de los 29 "Young Influentials in branding" de AdWeek, también trabaja con una selección de marcas que aparecen en DTX. En sus palabras: "No tuve ninguna marca que lograra ningún aumento". Sin embargo, hubo comentarios positivos. Según la fundadora de Andie , Melanie Travis, "[DTX Company] me había pedido que no compartiera cifras todavía, pero estoy entusiasmada con los primeros resultados". Según Google Trends, el interés por las búsquedas de Andie Swim alcanzó su nivel más bajo en siete días, el viernes de DTC.

Para quienes siguen la trayectoria de la empresa DTX, ha abundado el escepticismo. Ya he mencionado la composición del equipo de Armstrong. De los 29 empleados, cero han sido antiguos fundadores de marcas nativas digitales. Hay poca o ninguna experiencia práctica entre las paredes de una empresa encargada de revolucionar la captación de clientes para DTC. Hay poco del instinto que ha llevado a ciertas marcas a valoraciones y salidas desorbitadas.

En cambio, para preparar a Rimowa , competidora de Away, para la era DTC, LVMH contrató al antiguo fundador de Raden, Josh Udashkin, poco después de que su marca de maletas cerrara. Su experiencia práctica ha informado las decisiones tácticas de Rimowa durante más de dos años. Es esta falta de experiencia práctica lo que convenció al fundador de Lean Luxe , Paul Munford, para hacer este mordaz comentario:

Por lo que tengo entendido anecdóticamente, el viernes de DTC fue un fracaso. ¿Estoy sorprendido? No. Me acobardé cuando me enteré de que se iba a celebrar y, desde luego, no parece encajar con el espíritu del espacio de la DNVB. Parece que hay una gran arrogancia aquí al pensar que sólo por decretar esto como un nuevo día festivo, se convertiría instantáneamente en un evento masivo como el Black Friday para las DNVBs, que es una motivación horrible por sí sola.

Ahora entiendo la necesidad de un mercado centralizado para el espacio. Y creo que DTC Friday debía desempeñar ese papel. Pero la ejecución parecía fallida, no parecía haber un esfuerzo cohesivo en el lanzamiento, y he oído comentarios contradictorios de la gente que participó.

En mi opinión, no fue un fracaso. A pesar de los malos comentarios de algunos operadores de marca, el viernes de DTC probablemente cumplió su propósito. Tim Armstrong no se equivoca, se adelanta. El esfuerzo de DTX para lanzar el DTC Friday 2019 no fue diseñado para priorizar las marcas anunciantes. El objetivo era publicitar Flowcode, un rebrand supuestamente avanzado del concepto de código QR que fue descartado en los Estados Unidos, hace varios años. La estrella de cada uno de los anuncios de televisión, carteles callejeros y esfuerzos de listas blancas de influencers de la fiesta minorista no eran trajes de baño, ropa masculina de tejido técnico, ropa infantil o una bebida relajante. Tampoco eran las estrellas los propios fundadores.

En cada caso, la propiedad más destacada de cada anuncio era el Flowcode de Armstrong. DTX discriminó en sus inversiones publicitarias. Mientras que algunas marcas no experimentaron ninguna o muy poca mejora, hay pruebas que me llevan a concluir que una selección de marcas recibió el tratamiento real. Y se beneficiaron de ello. La petición de silencio de Andie tiene más sentido en este contexto.

Gasto estimado de Armstrong en Rockets of Awesome: 35.000 $.

Gasto estimado de Armstrong en Andie: 45.000 dólares.

Gasto estimado de Armstrong en Ródano: 27.000 $.

Gasto estimado de Armstrong en Recess: 65.000 $.

Flowcode, cultura QR y penetración del comercio minorista en línea

El comercio se ha democratizado y, gracias a plataformas como Facebook y Google, la atención se ha centralizado. Según el Presidente y Director de Operaciones de Loop Returns:

A medida que la atención se descentralice, las marcas tendrán la oportunidad de construir canales de comunicación DTC con los consumidores. DTX y Flowcode parecen un experimento temprano en este género. Puede que no acierten (es probable que no lo hagan), pero eso no significa que se equivoquen.

Vale la pena mencionar que cuando Tim Armstrong hizo los comentarios (abajo), fue malinterpretado por muchos.

La estructura de distribución de las redes sociales, las búsquedas, YouTube y sus formatos publicitarios permiten a estas empresas poner todo lo que tienen en su catálogo de productos directamente delante de los consumidores. El espacio de pagos, aunque complicado ahora, está a punto de volverse mucho más fácil. Y los sistemas que se están construyendo ahora permiten a las empresas establecer relaciones directas y en tiempo real con los consumidores.

Armstrong mantiene un notable desdén por la influencia de las FAANG en los medios de comunicación y el comercio, un hecho que sale a relucir en cada bocado sonoro o artículo sobre su trabajo con DTX. Sus soluciones son sólidas, pero incipientes. Aunque hemos visto grandes mejoras en los sistemas de pago en Norteamérica con la adopción de Apple Pay, Android Pay, Square Cash, Venmo, la llegada de Amazon Go y la expansión de otras soluciones digitales, Estados Unidos sigue por detrás de China y otros países asiáticos.

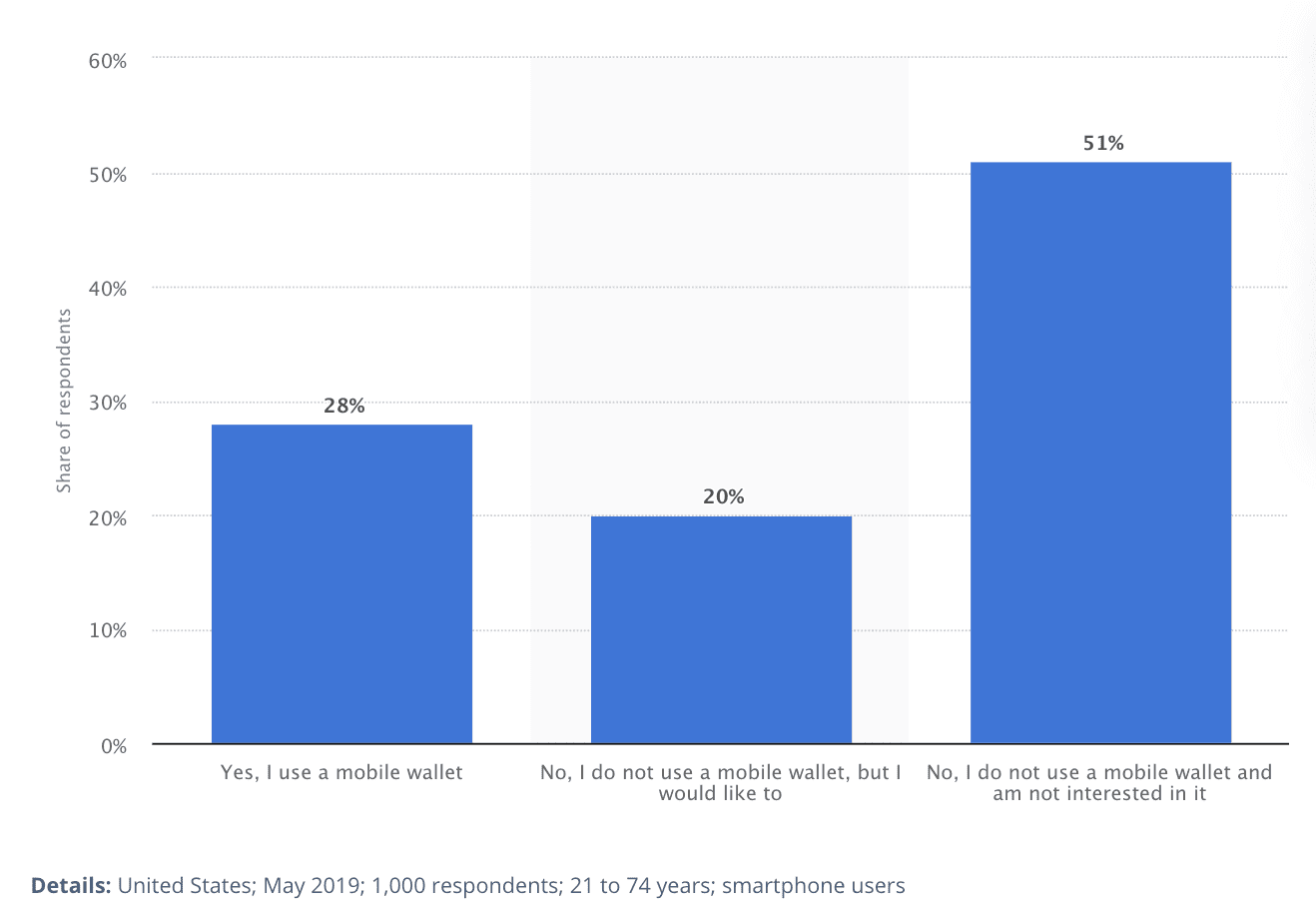

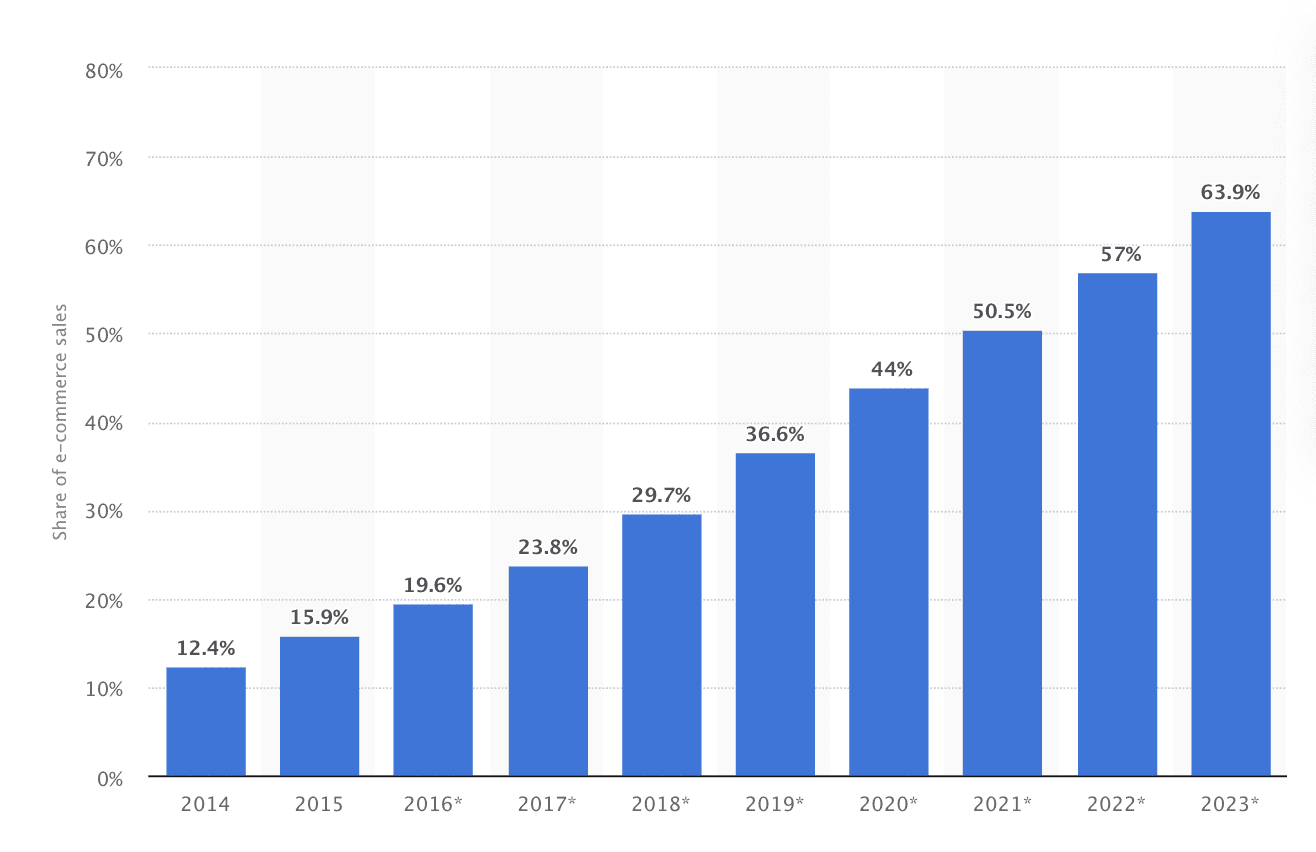

El comercio electrónico, un indicador rezagado, sigue representando un escaso 12% del total del comercio minorista en Estados Unidos. En comparación, esta cifra roza el 39% en China. La principal diferencia entre los dos índices de penetración puede atribuirse a la adopción del monedero móvil. En China, casi todos los ciudadanos utilizan los pagos móviles en su vida cotidiana. En el país, WeChat Pay y AliPay están tan extendidos que a los turistas les resulta difícil realizar transacciones sin ellos.

Los viajeros han tenido más suerte con Alipay, que introdujo la semana pasada un proceso de siete pasos que exige a los visitantes enviar a Alipay información sobre el pasaporte y el visado, antes de cargar dinero con una tarjeta del extranjero en una tarjeta prepago.[2]

Y he aquí por qué los datos son importantes. La atribución de offline a online ha sido difícil para los profesionales del marketing. En Estados Unidos, la atribución offline se realiza principalmente de forma manual para vallas publicitarias, folletos, publicidad por correo y activaciones físicas. Las marcas realizan encuestas o solicitan datos de atribución. En China, sin embargo, los códigos QR impulsan las ventas y la atribución a escala[3]. [3] Dado el flujo de innovaciones en el comercio minorista de China a Estados Unidos, está claro que cuando Armstrong habla de "facilitar" los pagos, anticipa la adopción de carteras móviles y sistemas de pago simplificados. ¿Por qué? La prevalencia de estos sistemas se correlacionó con una adopción masiva del uso de códigos QR en China.

A principios de esta década, la mayoría de los chinos seguían llevando dinero en efectivo a todas partes y las tarjetas de crédito apenas se utilizaban fuera de las grandes ciudades. Pero cuando la gente empezó a ganar más, estaba claro que necesitaba una nueva forma de pagar sin llevar fajos de billetes.[3]

Puede que el viernes de DTC no haya sido un día de ventas exitoso para la mayoría de los estándares, pero fue una forma eficaz de reclutar marcas populares para comercializar un concepto del que Estados Unidos se reía tan solo unos años antes.

En Estados Unidos existen barreras para el futuro que imagina Armstrong. Aquí, América está sobre-vendida. Hay más tiendas de ladrillo y mortero, per cápita, que en cualquier otro lugar de la Tierra. La industria del desarrollo inmobiliario es tan predominante que el ladrillo y el mortero se han convertido en el mayor obstáculo del comercio electrónico. Somos menos propensos a adoptar los pagos móviles y cuando podemos utilizar tarjetas de débito en la mayoría de las tiendas físicas.

Así que, mientras tanto, lo mejor es que las marcas nativas digitales aprovechen los métodos de los minoristas tradicionales para alcanzar escala. Sin embargo, la hipótesis de Armstrong acabará siendo cierta. El tiempo dirá si es la empresa DTX la que vive para llevarse el mérito de este cambio en el comportamiento de los consumidores. La curva de difusión de la innovación no favorece a Armstrong. Dependerá de DTX y de su banda de leales al DTC, como Andie, Recess, Rockets of Awesome y Rhone, persuadir a los millennials entendidos para que cambien su comportamiento de compra. Si no, Flowcode de Armstrong podría ser el Webvan de DoorDash o UberEats de otro innovador. El tiempo y la velocidad de adopción determinarán quién se lleva el mérito de la venta. Y ese puede ser un problema de atribución que ni siquiera Armstrong puede resolver.

Investigación e informe de Web Smith | Sobre las 2PM