Sometimes, the idea can be right. The strategy can be sound. And the tactic to implement the strategy, with the aim of achieving the big idea, can be incomplete at best or ill-advised at worst. This is how I perceived the Bud Light controversy, one exacerbated by a deepening cultural divide defined by race, gender, ethnicity, and even geography.

Anheuser-Busch is based in St. Louis, Missouri. The Bud Light marketing team is conveniently located in New York City. I suspect that the two arms of the organization failed to communicate beyond the big idea (reach more consumers, be more inclusive) and strategy (appeal to non-core customers). Two corporate cultures, two cities, two disparate meanings of “non-core,” and – likely – a difference in how that mandate should be met.

Alcoholic beer consumption is an American pastime that rises and falls with the times. In some ways, the preferences for it are out of the control of those most responsible for its sale and distribution. The rise in popularity is sometimes self-induced; other times, the fall in popularity can be self-inflicted. But, history has shown, it always bounces back.

In 1770, the average “American” drank 3.5 gallons of alcohol per year. By 1790, that number rose to 5.8 gallons. It peaked at 7.1 gallons in 1830. It varied between 1.7 and 2.5 gallons between 1850 and the beginning of World War I. And then Prohibition was enacted. According to the National Library of Medicine:

Prohibition reduced per capita consumption to its lowest level in U.S. history, probably less than 1.5 gallons. Since about 1960, per capita consumption has again been rising, with a particularly marked acceleration in the 1960s.

Today, the per capita consumption hovers between 2.2 and 2.5 gallons per year on average, returning to pre-Prohibition levels of consumption. And keep in mind, this isn’t gallons of beer, wine, or spirits. This is gallons of the alcohol within those beverages. That is a lot of pure alcohol. As F. Scott Fitzgerald, the great author and Prohibition Era writer, once wrote:

First you take a drink, then the drink takes a drink, then the drink takes you.

Fitzgerald, perhaps my favorite author, died of an alcohol-induced heart attack at the age of 44. He wouldn’t live to see his explosion of post-WWII fame (when The Great Gatsby popularized the writer beyond his wildest imaginations). This is the story of America’s great pastime. We drink to cope, we drink to celebrate, we drink to create, we drink to numb. Budweiser has been around for a lot of those ebbs and flows in America’s relationship with hoppy, brewed drinks. And as a result of that pastime of ours, Anheuser-Busch (Budweiser’s parent company) is worth nearly $120 billion (though down 50% from its 2016 peak).

Leading the team responsible for driving demand for a product with multi-century history is an unenviable position. And the headwinds of the present are, in some ways, as unique and damning as the Prohibition era that defined Fitzgerald’s writings.

A short history of the drink

The alcohol industry has long been a staple of the American economy and social scene, with different trends emerging, morphing, and subsiding over the decades. The early 19th century was marked by a growing trend of beer consumption, primarily driven by an influx of immigrants from beer-drinking countries such as Ireland and Germany. This period marked the establishment of many breweries, paving the way for the emergence of brands like Bud Light in the subsequent years.

The alcohol industry witnessed a period of contraction during Prohibition (1920-1933), a constitutional ban on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages.

The most radical attempt by the government to influence drinking in the United States came in the years 1920 to 1933, when the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution brought about Prohibition by banning the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages. Although majorities voted for Prohibition, many people were opposed or indifferent to its enforcement, and the years of the “noble experiment” were a time of widespread and flagrant abuses of the law. But after its repeal by the 21st Amendment, Prohibition came to have a much broader meaning in the public consciousness. (NLM)

The post-Prohibition era saw a swift rebound of the industry, and by the mid-20th century, beer had solidified its place as the drink of choice for the average American.

Bud Light, introduced by Anheuser-Busch in 1982, quickly rose to prominence as an easy-drinking beer that appealed to a broad demographic. However, from 1982 to 2023, the overall consumption of alcohol, especially beer, started to see a steady decline. A rising health and wellness trend significantly contributed to this shift, with more consumers becoming conscious of the negative health impacts of alcohol consumption. Consequently, the average American’s drinking habits began to evolve, with many shifting to healthier alternatives, lower-alcohol substitutes, or reducing their alcohol consumption altogether. We’ve explored this idea by studying non-alcoholic import data.

According to IWSR Drinks’ Market Analysis, a data and intelligence company that tracks worldwide alcohol trends, non-alcoholic drink products increased 22.6% in 2020 and is expected to grow over the next four years. IWSR anticipates a CAGR of 9.7% in this market through 2024.

The Current State of Light Beer

By the time Alissa Heinerscheid took the reins as Bud Light’s marketing head, the first woman in the brand’s four-decade history to do so, the task was not a simple one. You have to understand this. Bud Light had been grappling with long-declining sales, thanks to macroeconomic factors and changes in consumer preferences and behaviors. The challenge was to revive the brand’s popularity and appeal to a broader audience, including women and younger adults.

One of Heinerscheid’s ways to do so was a partnership with TikTok creator Dylan Mulvaney, an influencer known for a TikTok series called “365 Days of Girlhood” that served as a platform for celebrating Mulvaney’s transition from male to female (here is a great deep dive by the NYT). Mulvaney became a litmus test for one’s political leanings, drawing both ardent support and vehement disapproval from those who opposed and, then, those who approved. The first group boycotted Bud Light for supporting Mulvaney. The second group boycotted Bud Light for not supporting Mulvaney. The impact was significant:

Sales of Bud Light fell 17% in the week ended April 15 compared to the same week in 2022, according to an analysis of NIQ data compiled by Bump Williams Consulting provided to the Wall Street Journal. That same week, sales of rival beers Coors Light and Miller Lite each grew nearly 18% compared to the same week a year earlier.

The tactic (recruiting Mulvaney) used to address Heinerscheid’s mandate to expand the core customer of the brand reflected cultural changes that have become more mainstream in recent years. This mainstreaming of culture stands in opposition to Bud Light’s core business, which traditionally catered to a demographic often represented by a rural distributorships, conservative-leaning men, family wholesalers, and southern customers. These individual distributorships, of the 3,000 beer distributors in the United States, are led by people like Steve Tatum, General Manager of Bama Budweiser:

“We at Bama Budweiser, an independent wholesaler, employ around 100 people who live here, work here, and our children go to school here,” he said in a recent ad commissioned to help win back business that Bud Light has lost in recent weeks.

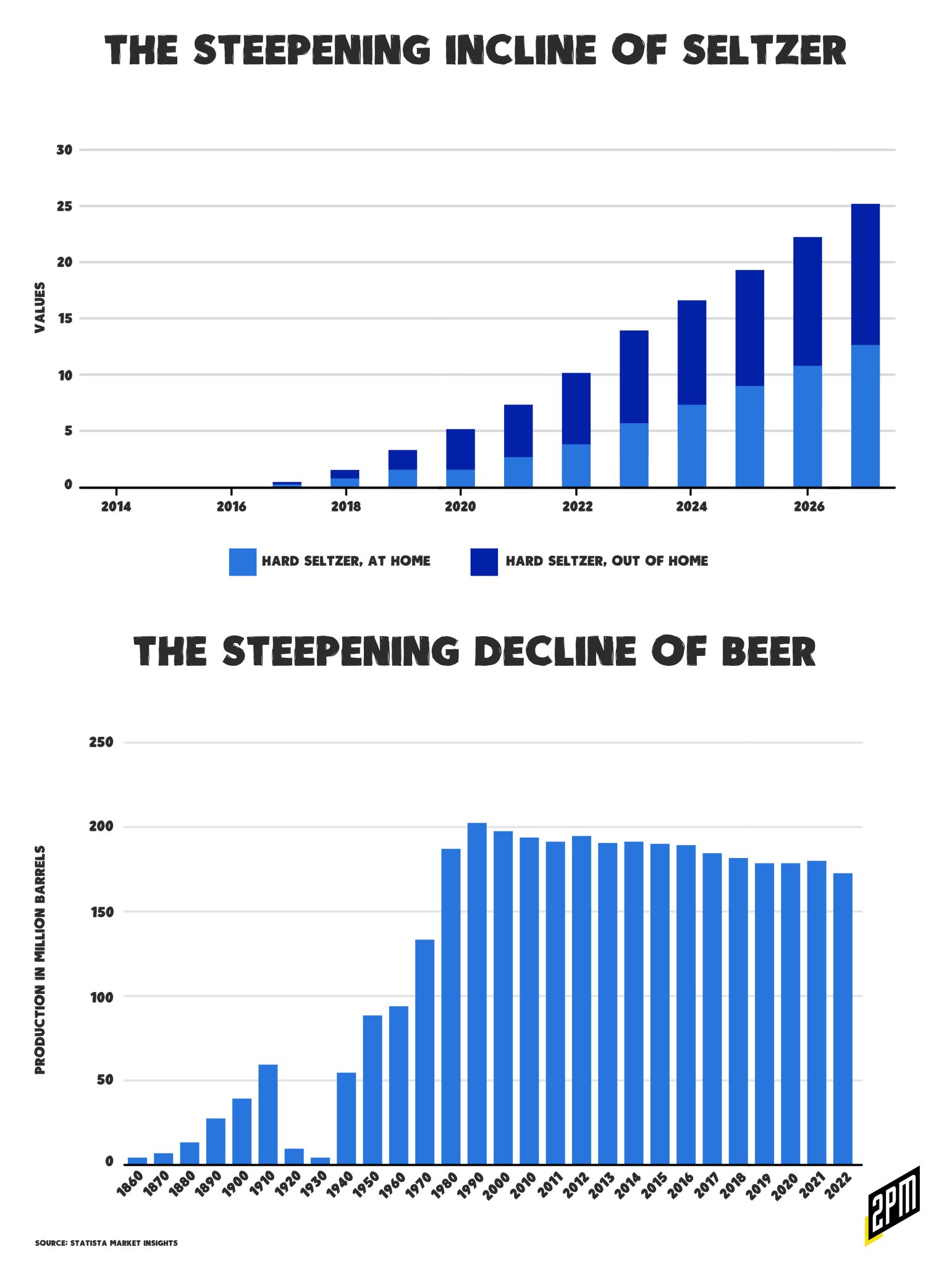

Tatum has been at Bama Budweiser since 1989; he’s probably seen quite a bit of the natural cycles involved with selling beer to grocery stores and independent retailers. He’s never seen a month like this, however. This unofficial partnership between Bud Light and Mulvaney coincided with the continued overall decline in light beer sales, as alternatives like hard seltzers and other alcohol forms gain popularity, thereby further complicating the dynamics at play. In response to the April 1 influencer campaign, Budweiser slowly responded two weeks later.

We’re honored to be part of the fabric of this country. Anheuser-Busch employs more than 18,000 people and our independent distributors employ an additional 47,000 valued colleagues. We have thousands of partners, millions of fans and a proud history supporting our communities, military, first responders, sports fans and hard-working Americans everywhere. We never intended to be part of a discussion that divides people. We are in the business of bringing people together over a beer.

By the second week of May, Bud Light sales were down 28% YoY according to a Bump Williams analysis of Nielsen data. So this week, Bud Light worked to minimize further damage by emphasizing one of the traditional partnerships that have come to define the brand and its millions of customers.

While clearly informed by cultural norms that may not have been shared by the entire company, Heinerscheid’s rationale was not without merit. Her big idea was sound, her strategy was traditional, given the time and place. The tactic was flawed and she was immediately scapegoated for the disconnect that is likely at issue at the c-suite level, as well. The trend towards alternatives was clearly on the rise, and Bud Light did need to adapt to changing times and changing competitors. Non-alcoholic beer and lower alcohol alternatives are a growing preference for health-conscious men and women according to recent MediaPost data. And this is only one of the key industry changes that Heinerscheid was likely dealing with:

However, the decision to feature Mulvaney failed to take into account the perception of the brand’s perceived social values and the corporate structure of the business (Bud Light depends on hundreds of independently owned distributorships). This means hundreds of opinions, many of which were in opposition. This oversight neglected to acknowledge the deep-seated attachment and almost religious-like devotion some customers had towards Bud Light’s traditional products. In the 1993 movie The Program, one character was named “Bud-Lite Kaminski.” This was but one of Bud Light’s many marketing decisions that succeeded in that era.

The partnership with Mulvaney, combined with the broader macroeconomic conditions of declining alcohol consumption, increased substitutability (Coors and Miller Lite benefited greatly), while competition from the likes of Coca-Cola amplified each other’s effects, leading to further contraction in Bud Light’s sales.

Coke’s expansion into alcohol arrives as its core portfolio of sodas and other beverages continues to see demand recover from the depths of the pandemic.

It’s been a perfect storm that the brand was not fully prepared to weather.

The Rich Heritage, The New Marketing Strategy?

Moving forward, however, it is crucial to remember that setbacks can pave the way for innovation. For Bud Light to regain its lost ground, it needs to embrace the changing landscape while honoring its rich heritage. A potential way forward could be a direct-to-consumer business model, which could shield the brand from the wholesalers’ whims and provide a more direct line of communication with its customer base. In a way, it could move some of the business’s core from St. Louis to New York City (where more decision-making power needs to reside).

The direct-to-consumer approach would allow Bud Light to control its narrative better, and more importantly, tailor its offerings and marketing strategies to align with its consumers’ evolving preferences. The growth of the model (as regulations allow) could provide the flexibility necessary to experiment with new products while maintaining the quality and appeal of its traditional offerings.

AB InBev drives much of its ecommerce from the mobile app and ecommerce platform the company calls BEES, at BEES.com. “BEES is live in 20 markets, with approximately 63% of our revenues now through B2B digital platforms,” the company says. “In FY22, BEES reached 3.1 million monthly active users and captured approximately 32 billion USD in gross merchandise value (GMV), growth of over 60% versus FY21.”

However, a direct-to-consumer approach will require Bud Light to effectively leverage digital channels for marketing and sales. The brand will need to invest heavily in developing a system for managing data analytics that will help executives better understand consumer behavior. This would mean more of the team would shift away from the traditional office in St. Louis to the New York office that felt more comfortable with Mulvaney’s partnership (according to reports).

While it is essential to embrace changing societal norms and support diversity, the brand should ensure that its partners reflect its core demographic. A more inclusive and diversified marketing strategy can be achieved without alienation of new or existing customers.

Bud Light should not neglect its traditional light beer category while pursuing alternatives like non-alcoholic beers and seltzers. The data shows a cyclical market for traditional products. Seltzers, cocktails-in-a-can, and other products in the alcoholic category will rise and fall in popularity; light beer will remain. Remember Smirnoff Ice, anyone? Bud Light’s alternatives can be offered under a new sub-brand to differentiate them from traditional Bud Light products, thereby preserving the core identity of Bud Light while allowing for innovation and expansion to reach the customer base that Bud Light will need to grow into the future.

Bud Light should also consider emphasizing its commitment to responsible drinking and overall wellness. This could involve spending more of its marketing budget on zero-alcohol versions of its products, promoting the enjoyment of beer without the associated health risks. This will demonstrate the brand’s adaptation to the growing wellness trend and potentially attract health-conscious consumers. AB Inbev, which owns Corona, Michelob, and Modelo, had previously mentioned a goal to achieve 20% of “its beer volume non-alcoholic and low alcohol by 2025.” Budweiser actually perfected this very-low/no-alcohol strategy during the 1920s. They called it Bevo, a play on the Bohemian word for beer: “pivo.” More than 50 million cases were sold annually across 50 countries.

And then there was Bevo, a clever strategic movement of Anheuser-Busch that introduced the near beer brand to the American people. Bevo initially was introduced to the United States Armed Forces, which already had to deal with an alcohol ban in 1916. Thus, Anheuser-Busch was able to push the product nationwide during the prohibition in 1920 and provided anyone who wanted to have a close-to-beer experience with Bevo. Anheuser-Busch also heavily invested in the Marketing of Bevo as the ads, but also the merchandise example does show, see below. Only a few years before the end of the ban, the production of Bevo was discontinued in 1927, which makes Bevo truly a prohibition phenomenon.

The challenges Bud Light faces are indeed daunting, but the challenges also present an opportunity for reinvention and growth. With a carefully calibrated approach that embraces the new while respecting the old, Bud Light can not only weather this storm but emerge from it stronger and more relevant in today’s changing social, political, and consumer landscapes. It begins with an idea, one developed into a shared strategy, and then with tactics that the entire company can rally around. It was the short distance from strategy to tactics where Bud Light erred. And while it was easy to scapegoat a few executives, the fiasco revealed much more about the disconnect between the logistics side of the business, its front offices, and the human resources responsible for generating demand in this fast-changing world.

Bud Light will bounce back and continue its legacy as a beloved beer brand; this is just another down cycle. Even Prohibition was no match for its innovations. Bevo succeeded as an alternative and kept the business alive while Prohibition was enacted to destroy it. The idea matched the strategy and the tactics helped employ the strategy. This fluid connection between the ones and the others helped a doomed company survive. Beer always does survive; the consumer always comes back around. Nothing was worse than Prohibition. And 100 years later, the company is alive to tell the tale.

And there’s the new ad campaign, in and of itself.

By Web Smith | Edited by Hilary Milnes with art by Alex Remy and Christina Williams