Om Malik and Lean Luxe‘s Paul Munford had a thought-provoking exchange. Does the modern luxury go-to Lean Luxe (and the industry as a whole) have a grasp on what luxury means in online retail? On its face, a physical product that makes itself available to the masses cannot be a luxury product.

Lean Luxe on Twitter

@om Sure, by the old definition of luxury – you’re correct. But don’t judge modern luxury brands’ bonafides using the old set of luxury rulebooks. More here: https://t.co/ZLjoBdxYUz and here: https://t.co/uHYOPzsI9n

There are very few products, if any, that digitally vertical native brands (DNVB) sell that would qualify as traditional luxury goods. Here is Munford’s definition:

The key strength of a modern luxury brand is its emphasis on the entire package, rather just the product (or logo) itself. It’s a different mode of operation that takes some getting used to, but it disperses with the conventions of the old, blingy version of luxury, and is best optimized for today’s new consumer behaviors and expectations.

The fact of the matter is that competing on product quality alone leaves a brand open to exposure. MLCs have smartly understood that a better overall package or bundle — in an open market like today’s — can be far more compelling to shoppers than just product alone can.

Munford makes an important point that I’d like to take a bit further. Lean Luxe tends to maintain a narrow focus on hard goods and the packaging that they arrive in. But what about the purchase process and the attentiveness to customer happiness? And what about time?

The definition of luxury: an inessential, desirable item that is expensive or difficult to obtain.

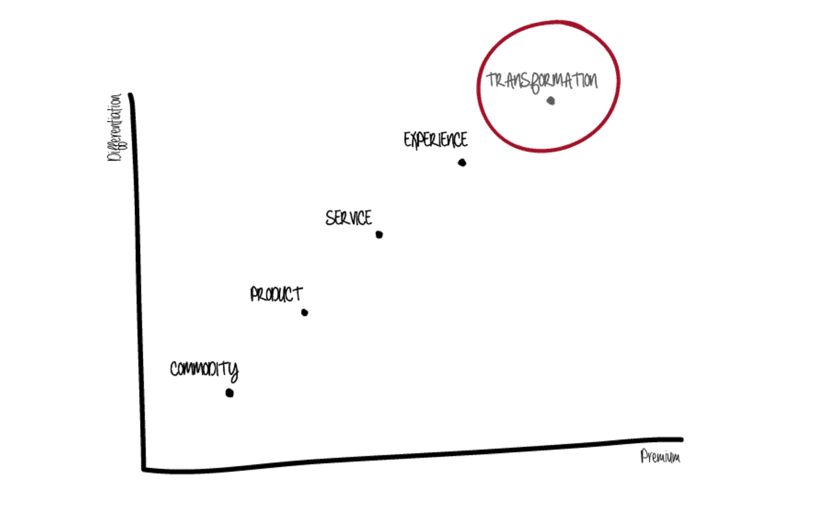

Luxury, however you define it, is a brand’s embodiment of characteristics that make it desirable. Historically, those characteristics have been more ‘What’ features like quality, exclusivity, and cost. You can still define luxury as characteristics that make a brand desirable, but those characteristics have shifted. Quality is table stakes.

使品牌更受歡迎的特點是"如何"功能,如優秀的客戶體驗(我如何體驗品牌)、有意義的品牌使命(他們如何回饋/改變)和社區參與。是藝術家創造的, 價格太貴嗎?也許不是但是,如果它是一個產品,甚至整個經驗,是非常可取的,它可以被認為是一個豪華的品牌。DNVB 恰好擁有強大的基礎設施,以支援定義現代奢侈品的特徵。

Luxury is always relative; it is loosely defined to meet the times and the market. If you walk through a great mall in the United States, you will visit brand experiences that will provide a luxurious taste. Take Ohio’s Easton Town Center as an example. The indoor / outdoor mall features Burberry, Tiffany and Co., and Louis Vuitton. However, your perception of luxury changes when you walk through the Bal Harbour Shops in North Miami Beach. Bal Harbour is considered the finest mall in America. Both malls are considered “luxury” malls but neither are as luxurious as Dubai’s mall.

But can a DNVB be a luxury brand?

The notion of luxury is often applied to tech fashion brands. I partially agree with Om Malik’s statement here.

[Lean Luxe] is again confusing smoke / mirrors marketing and what is really luxury. All I know is that AllBirds and Brandless and Casper are not luxury, And no amount of your linguistic gymnastics will convince me of what is luxury, FWIW, LV is not luxury either. Too common.

AllBirds, Brandless, and Casper do not make luxury products but Munford isn’t suggesting that their products-alone are what classifies them within the modern luxury space.

Louis Vuitton was first hired as a personal box maker and packaging expert for the Empress of France. He was charged with “packing the most beautiful clothes in an exquisite way.” It was the practice that helped him to gain influence among the elite and royals, catapulting Louis Vuitton’s namesake to luxury status.

Louis Vuitton began with an early product and the two advantages commonly seen in the DNVB space:

- Packaging

- Maniacal focus on customers

The definition of a DNVB: a brand born online with a “maniacal” focus on the customer experience. A DNVB may start online but it often extends to a brick-and-mortar manifestation. Digitally native vertical brands control their own distribution.

Luxury brands don’t always begin as purveyors of luxury products. And due to a macroeconomic consumer shift from materialism to investing in luxury experiences, there are a large number of consumers who prefer DNVB’s luxury-experience over traditional luxury products. For many in the business and wealth classes, it’s a symbol that their money is better spent on even finer things than goods. The definition of luxury is changing.

Here are two relevant passages from 1994’s The Idea of Luxury:

Page 18

Page 35

Buying experiences over buying consumer goods is a trend being adopted by the luxury-set. The interpretation of the word luxury means something altogether different for the types of customers who have the means and awareness to shop with DNVB brands. Skift’s latest research shows a clear shift in demand for more transformative travel experiences among upscale travelers (Skift / May 2, 2017). Whereas expensive products used to be the consumer desire: products, community, and service now play the role of enabling experience economy.

Many DNVB products (see the database here) are marketed to enable this type of consumer: Mizzen+Main (No. 86) is for the traveling business class male. Ministry (No. 91) is for the well-educated, urban millennial. AllBirds (No. 56) is worn by the business casual, aspiring member of the investor-class. Rogue (No. 8) turned a garage into a coveted space in a home.

Digitally vertical native brands are founded with these basic questions:

(1) How do we make a great product?

(2) How do we build a community around it?

(3) How do we provide an elegant solution for commerce?

(4) How do we enable customers to save time and focus on what matters?

“One fundamental trap that people run into when assessing the merits of a modern luxury brand is the tendency to judge that brand using the ‘best-in-class’ framework,” says Lean Luxe’s Paul Munford. Lean Luxe’s definition is mostly right. Munford discusses packaging as part of the bundle: “[These brands] offer a better bundle to offset [traditional definitions of luxury] — more convenience, transparency, connection, better messaging, pricing, etc.”

But a selection of modern luxury brands are also marketing time as part of the proverbial “bundle” and that’s the only place where Munford and my thoughts differ.

用奢侈品的難點來定義它們已經不夠了。時間是最稀缺的資源,也是終極的奢侈品。做一個現代奢侈品牌就是要有自我意識。這些品牌將時間作為稀缺性出售,然後圍繞它構建產品。

There may be no greater example of the community / product / service paradigm than Peloton, a DNVB that Malik’s True Ventures joined back in 2015.

Peloton is now shifting gears with a new financing program ($97 per month for 39 months for both the bike and subscription service), an ad campaign that’s more relatable to a diverse consumer base and an NBC Olympics sponsorship. Peloton counts NBCUniversal among its investors, and has raised nearly $450 million in total funding to date.

“We had this idea of a very affluent rider who many of our early adopters were,” she said. “We realized, through conversations with our community, that there was a huge opportunity with people who thought $2,000 was a huge investment but were [buying] it over and over again because the product is so important to them.”

How Peloton is Marketing Beyond the Rich

佩洛頓不是傳統的奢侈品,但它與傳統奢侈品牌共享消費者。想想容納一輛支援 wi-fi 的自行車或一台價值 4,000 美元的 VR 跑步機所需的生活安排類型。這是一個輝煌的硬體,將社區與產品和服務融為一體。該品牌的主張明確指出,目的是讓擁有者更專注於體驗。

Peloton’s value proposition is as much about what you can accomplish away from the treadmill. Why take the time to travel to a gym? That time could be better spent elsewhere. This is the mark of a modern luxury brand.

在這裡選擇閱讀更多問題。

By Web Smith and Meghan Terwilliger | About 2PM

[…] Issue No. 265: Can A DNVB Achieve Modern Luxury […]

[…] Issue No. 265: Can a DNVB achieve modern luxury? […]

[…] Additional reading: Can a DNVB Achieve Modern Luxury? […]

[…] Issue No. 265: Can a DNVB Achieve Modern Luxury? […]

[…] No. 265, we discussed this in the context of Peloton, the in-home cycling and media phenomenon that shares […]